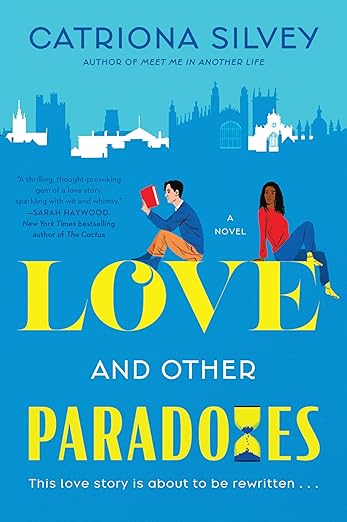

Today, HJ is pleased to share with you Catriona Silvey’s new release: Love and Other Paradoxes

One of the greatest love stories in history gets derailed when a struggling poet at Cambridge runs into a time-traveler who agrees to help him find his muse—a thoughtful and uplifting romantic comedy for fans of About Time and The Midnight Library.

Then, the future quite literally finds him—in the form of Esi. She’s part of a time-traveling tour, a trip for people in the future to witness history’s greatest moments firsthand. The star of this tour? Joe Greene. In Esi’s era, Joe is as renowned as Shakespeare. And he’s about to meet Diana, a fellow student and aspiring actress, who will become his muse and the subject of his famous love poems.

But Esi is harboring a secret. She’s not here because she idolizes Joe—actually, she thinks his poetry is overrated. Something will happen at Cambridge this year that will wreck Esi’s life, and she’s hell-bent on changing it. When Esi goes rogue from her tour, she bumps into Joe and sends his destiny into a tailspin. To save both their futures, Esi becomes Joe’s dating coach, helping him win over Diana. But when Joe’s romantic endeavors go off-script—and worse, he starts falling for Esi instead—they both face a crucial question: Is the future set in stone, or can we pen our own fates?

Enjoy an exclusive excerpt from Love and Other Paradoxes

Joe stood in the hush of the Wren Library, looking up into the marble eyes of the poet.

The poet was lounging on the ruins of an ancient Greek temple, foot drawn up to rest on a broken pillar. One elegant hand pointed a pencil to his chin; the other held a finished book of poems. The poet’s handsome brow was furrowed, his eyes fixed on the middle distance. Joe found himself unconsciously mimicking the pose: raising one hand, setting his jaw, staring across the black-and- white tiles of the library floor. A girl sitting in an alcove looked up and met his eyes. Thinking he was looking at her, she smiled. He was about to smile back, then remembered he was supposed to be looking intense and poetic. He frowned, shifting his gaze to the stained-glass window. When he glanced surreptitiously at the girl, she had gone back to reading.

“Lord Byron,” said someone behind him. “He was a student here, you know.”

Joe flinched in surprise, then fell back into his usual apologetic slump. The speaker was one of the black-uniformed men who were an everyday feature of Cambridge life. They were called things like porter or proctor or praelector, and seemed to appear from nowhere. He had a theory that they seeped spontaneously out of the marble whenever you stood still for too long.

“I know,” he replied. That was why he was here: to remind him- self that Byron had once stood where he stood, which meant that achieving his own destiny as a great poet was not completely out of reach. Byron, of course, had not been looking up at a statue of himself, unless, alongside writing poetry and having sex with a lot of people, he had also invented time travel.

“Kept a bear in his room,” said the black-uniformed man. “Legendary lover, of course,” he added.

Joe felt a laugh creep up inside him. “The bear?”The man was looking at him with a mixture of pity and disappointment. “Are you a member of the college?

He tensed, confronting the spectre of not-belonging that had haunted him for the past two years. “No. I mean, I’m a student, just—not at Trinity.”

The man patted him heavily on the shoulder. “Then I’m afraid I’ll have to ask you to leave.”

Outside, the autumn sun glinted off the dew-damp grass. A chill October wind blew up from the river, cutting through his cheap coat. He hurried through the insane, stage-set grandeur of the college, so different from the squat fishermen’s cottages he had known for the first eighteen years of his life. Now, at the beginning of his third year as a student, he had almost stopped noticing it. It only came clear to him at moments like this, when he confronted the reality that in eight short months, he would be graduating. He would be cast out, like an orphan stumbling from Narnia back into wartime England—or in his case, rural Scot- land, back to his job at the village pub, with no proof that his time here in the other world had been anything but a dream. Unless he could find a way to prove that he had always belonged here, among the historymakers; that letting him in had not been a terrible, embarrassing mistake.

As he left Trinity through the vaulted archway of the Great Gate, he was so lost in thought that he walked straight into someone.

“Sorry,” he blurted, looking at the person he’d almost knocked over. A girl, pale-faced, with unusual light green eyes. She had swept her dark hair to one side, in the way all the posh girls here did, as if they were in a strong wind no one else could feel. Some- thing about her was familiar. He couldn’t understand why until he saw what was printed on her hoodie. Macbeth 2004. He had seen that show, last year at the ADC Theatre. She had played Lady Macbeth. He remembered her being blazingly, shockingly good, outshining the other actors like candles to her sun.

She raised an elegant eyebrow. He sensed the chance to say something, to change the future of this moment, but he couldn’t think of anything clever enough. The girl threw him a disdainful look and walked on.

He folded into himself, grimacing. “Byron wouldn’t’ve just stood there like a numpty,” he muttered. “Byron would’ve said something.” Out on Trinity Street, the late-morning light slanted down, turning the fallen leaves to splashes of gold. The back of his brain filed the details away to use later, even as the front of his brain brooded over the fact that he hadn’t finished a poem since he’d started his degree.

By Great St. Mary’s church, the usual tour groups were craning to look up at the tower. He was edging his way past when he saw with alarm that one of the groups was staring straight at him.

He stared back. Most of them looked away. One met his eyes and stepped forward. A girl with a strange, asymmetric haircut, dressed in the thousand-pocketed combat trousers that had been fashionable about five years ago. She was gazing at him in slack- jawed disbelief. He immediately worried that he had toothpaste around his mouth. As he went to scrub it off, someone pulled the girl away—an olive-skinned woman in her late twenties, brown hair tied back in a ponytail, wearing a tabard that marked her out as the tour guide.

“Time’s up.” She corralled the group together and ushered them away. He watched them dwindle down King’s Parade, the girl in the combats casting surreptitious glances over her shoulder. He made a mental note to look in a mirror as soon as he got back to his room.

Inside the stone walls of his own college, no one gave him a second glance. Reassured, he went by the post room to check his pigeonhole. Usually, it would have contained nothing but free condoms and flyers from the Christian Union, but lately, he had been finding it full of strange gifts. A single white rose; a fountain pen; a keyring with a quote from a poem that, when he looked it up, didn’t appear to exist. Today, there was a scribbled note that said simply, Thank you. With growing unease, he crumpled it into the recycling bin and headed up the stairs.College had a strict rule that shared sets of rooms were for friends, not couples, on the grounds that student romances were too unstable to last the nine months of the lease. Joe couldn’t fault their logic. He and Rob had been friends since first year, outliving his longest relationship to date by a factor of nine.

He climbed the staircase two steps at a time: after a summer on his feet serving endless pints to seaside tourists, he could reach the top without getting out of breath. He unlocked the door, blinking in the sun that spilled through the high windows. He loved his and Rob’s rooms, fiercely and completely. He loved the living room, with its sagging sofa and its blocked-off fireplace stacked with bottles of cheap wine; he loved his bedroom, with the window that opened onto a tiny stretch of battlements, the closest he would ever get to living in a castle. By inching along a narrow ledge and scaling a drainpipe, you could supposedly get to a secret terrace with a view of King’s College, but he had never tried: he was haunted by visions of falling, to be memorialised only by a snippet in the local paper lamenting his wasted potential.

Rob was technically studying physics, but his true passion was the mock-combat game known as Assassins. As Joe came in, he was fashioning a trebuchet out of old copies of the student news- paper, pink with concentration, sandy hair flopping over his face. “Morning, Greeney,” he said without looking up.

Joe muttered in nonresponse and went straight through to his bedroom. Flinging open his desk drawer, he threw out the toy Highland cow his Scottish mum had got him so he wouldn’t for- get his roots, the toy London bus his English dad had got him in retaliation, and the toy penguin his sister Kirsty had got him because “it reminded me of you.” Hidden underneath was a pile of notebooks scrawled with poems. He combed through them, searching for something he already knew he wouldn’t find. None of them—the epics he’d feverishly scribbled as a teenager, the fragments he’d forced out word by tortured word since coming to Cambridge—were remotely good enough. There was a fire in his brain, white-hot and unrelenting, but not a single spark had made it onto the page.

He groaned, burying his face in his hands.

“What are you moaning tragically about?” Rob called from the living room.He staggered out of his bedroom and collapsed face down onto the sofa. “I’ll never be a great poet,” he said into the cushions. “I might as well just sit in a bin and wait to die.”

“Surely there’s some middle ground between ‘great poet’ and ‘dead in a bin.’ What about a nice job in the civil service?”

“I’d rather be dead in a bin. Anyway, you need a good degree to get a job in the civil service, and according to Dr. Lewis, I’m not getting one of those.” He winced, anticipating what his Director of Studies would say tomorrow morning when they met for their weekly supervision. Failing out of his degree was a real and ever- growing possibility. He had nightmares about it sometimes: going home to face his parents’ poorly hidden disappointment, the smug vindication of everyone who’d thought he was an idiot for even applying.

“This is a radical suggestion, Greeney, but—why not take her advice? This is the only year that counts towards your final mark. Maybe it’s time to drop the poetry and focus on what you’re here for.”

Joe rolled over and stared at the ceiling. His family’s expectations, his diminishing overdraft, the loans he would somehow have to find a way to pay back, all agreed with Rob: the important thing was to graduate, so he could get a job and not have to live, or indeed die, in a bin. But he had only ever really wanted one thing, and the fact that it currently seemed impossible didn’t make it any less vital. “What about you?” He turned the question back on Rob. “Why don’t you stop pretending to kill people and focus on what you’re here for?”

“You know why, Greeney. Because I have to defeat my nemesis.”

“Aye, of course. The Deadly Mr. Darcy.” Joe had never actually met Rob’s nemesis. He only knew that they had fought a duel at the end of first year, which had ended in Rob’s death by blue confetti. “What’s your pseudonym again?”

“Entropy.” Rob struck a pose. “It’s going to get you in the end.”

“It’s not funny if you have to be a physicist to understand it.”

“Stop changing the subject. The point is, you don’t have a nemesis. What’s your excuse?”

He thought about looking up at the statue, a hundred and eighty years after the poet had taken his final breath, and the answer came easily. “I want to be remembered.”

It was a ridiculously grandiose thing to admit to. But Rob just nodded, as if it made sense. “Okay. So, be memorable. I thought you’d already started. Didn’t you win the Tartan Limerick contest, or whatever?”

“The Scottish Young Poet award,” Joe corrected him. “When I was fifteen. And what have I done since? I submitted a poem to The Mays in first year, and they rejected it for being ‘naive.’” That note still rang in his ears every time he sat down to write. “And see what I’m up against.” He grabbed a copy of Varsity from Rob’s pile and leafed through at random. “Here. Someone in second year who’s already been commissioned by the BBC.”

“Overachiever,” Rob scoffed. “Ignore them.”

“I can’t afford to ignore them. I’m the first kid from my school to go to Cambridge since anyone can remember. Everyone back home’s expecting me to, I don’t know, invent the moon or something.”

“Moon’s already been invented, Greeney. You’ll have to think of something else.”

“And poetry has always been my thing,” he went on. “It’s what I do. It’s like—like ”

Rob placed a hand dramatically on his heart. “Like breathing.” “No. It’s not like breathing. Breathing is boring, and easy, and everybody does it. Poetry is—it used to be fun, and hard in the best way, and it made me feel more like me than anything else.” He flushed: if he’d been talking to anyone but Rob, he would never have let the conversation get to this level of honesty. “I applied here because I thought it would turn me into the poet I’m supposed to be. But it’s the opposite. I think about all these great poets who came here before, and all I can see is how I just don’t measure up.”

Rob cleared his throat. “Greeney. Do you remember what happened when I joined the Assassins’ Guild in first year?”

“Someone shot you at point-blank range with a banana.”

“That is correct.” Rob steepled his fingers. “And how did I respond?”

Joe scrunched up his face. “Am I a bad friend if I don’t re- member?”

“I read the reports of every Game since Lent 1993, consulting the same hallowed archives in which I hope to one day be en- shrined as a Master Assassin. I learned the Game’s most important principle: make yourself hard to find. And, crucially, I kept playing. The result? While I’ve yet to win, I’ve survived till at least week five in every Game I’ve taken part in since.”

“Was there a point to this story?”

“The point is, you submitted to one pretentious student anthology and you didn’t get in. Big deal. Keep trying.” Rob reached in his pocket and took out a pink sheet of paper. He scrunched it into a ball, loaded it into his trebuchet, and fired. It hit Joe in the face and bounced off into a gap between the sofa cushions.

“Ow,” said Joe pointedly. He fished the ball out and unrolled it.

It was a flyer for a poetry competition. The title, surrounded by hearts, was Love Poems for Tomorrow. The idea was to pair emerging student writers and actors, who would perform the winning poems at an event on Valentine’s Day.

He imagined the hush of the ADC Theatre, his words echoing out from the stage. He visualised his future unfurling from that moment: a life of art and glory, where people knew his poems and treasured them, passing them down the years until the mess of his existence was overwritten by the perfect things he’d created.

“So?” Rob prompted him.

He sighed. “When’s the deadline?”

“Didn’t look. Must be on there somewhere.”

He found it at the bottom of the flyer. The first of November, 2005. Tomorrow.

The perfect, imaginary poem evaporated, leaving behind the terror of a blank page. Who could he write a love poem about? His first-year girlfriend, who had dumped him after three months when they had run out of things to say to each other? The girl he had kissed outside the toilets last time he went clubbing, who had slurred something in his ear about how much she loved Brave- heart, passed out on his shoulder, and never called him back?

“Oh no,” said Rob, recognising the expression on Joe’s face. “You’re having a Thought, aren’t you?”

The revelation built itself like a poem, elegant and inescapable, the end contained in the start. “This whole time, I was thinking, I can’t believe Rob is comparing my poetry to being in the Assassins’ Guild. I mean, you pretend to kill people, with banana guns and wee paper swords. It’s playacting. It’s a cheap, brazen mockery of anything real.”

“All right,” Rob muttered. “I don’t judge your hobbies.”

“And my poetry is exactly the same.” He spread his hands. “I’ve been sitting here trying to make a trebuchet out of old news- papers. Because I’ve never been in love.” It felt like looking up at the statue, recognising the immense gap between who he was and who he wanted to be. “That’s the problem.”

“No. That’s not the problem. The problem is that you’ve let this place get to you. I mean, you’re trying to write poetry while literally being stared at by the ghost of Lord Byron.”

He started. “How did you know?”

“You’ve got ink on your chin. You were doing that pen pose again, weren’t you?” Joe licked his finger and scrubbed. “Greeney. Stop reading Varsity. Stop staring at statues of insane aristocrats who had inappropriate relationships with their sisters.” An idea lit Rob’s face. “In fact, why not get away from the university? Go somewhere completely unexpected. Say . . . Mill Road.”

“This is starting to sound really specific.”

“Fine.” Rob tapped the wall chart that tracked his progress in the Game. “Truth is, I’ve got a target out at Hughes Hall, and I don’t want to walk there on my own.”

Joe sighed. “All right. But then I’m coming straight back to sit in a bin and wait for death.”

“Deal.” Rob checked his watch. “Oh. Give me a second.” He disappeared into his bedroom, emerging a few minutes later in a green waistcoat and straw hat.

Joe looked him up and down. “Is that your fancy murder outfit?” “Got a shift on the river at quarter to one. I won’t have time to change.” Rob had a technically forbidden part-time job as a punt guide, poling tourists along the river while telling them outrageous lies about the famous people who had attended Cambridge in the past. He clapped his hands. “Chop chop, Greeney. Those poems aren’t going to write themselves.”

Joe pocketed a blank notebook and the flyer and followed Rob out of college. Across the street, the woman in the tabard was watching him with bored intensity. As Joe turned left, she di- rected her group in parallel along the opposite pavement.

He leaned towards Rob, keeping his voice low. “See that woman?” “What woman?” Rob turned.

“Don’t look!”

“You want me to see without looking? I thought you were a philosopher.”

“And I thought you’d spent the past two years working on your stealth skills.”

Rob sighed as they turned up Pembroke Street. “I know you’ve just decided the crux of all your problems is that you’ve never been in love. But fixating on the first woman you see in the street is not a solution.”

“I’m not fixating. She’s fixating. She’s been following me around. Look! She’s got a whole group with her!” One of them raised a disposable camera and flashed a photograph. “They’re taking pictures of me!”

“Greeney, I’m not saying you’re delusional. But we live in one of the busiest tourist spots in Western Europe. Is it possible that instead of taking a picture of you, a random undergraduate, they were instead taking a picture of the stunning twenty-fourth- century court of Pembroke College, which is directly behind you?”

“Fourteenth century. I’m not on one of your tours; you don’t need to lie.” Still, he couldn’t shake the paranoia. “This, and all the weird stuff in my pigeonhole—there’s definitely something going on.”

Rob looked at him sideways. “Maybe I signed you up for Assassins without telling you and now everyone is out for your blood.”

“I can’t tell if you’re joking.”

“Course I’m joking,” Rob scoffed. “That would be absurd.”

He eyed the newspaper trebuchet under Rob’s arm. “Aye. That would be absurd.”

They crossed the grassy expanse of Parker’s Piece. With no sea to frame it, the sky felt too big, like a huge eye staring down at him. Only when they passed the lamppost known as the Reality Checkpoint, where the university gave way to the rest of town, did the feeling of being watched start to ease off.

“This is me.” Rob turned down a side street.

“Good luck with the murder,” Joe shouted encouragingly.

Someone walking past did a double take.

“Keep it down, Greeney. We’re in the real world now.” Rob turned back. “Don’t forget, it’s Halloween Formal tonight! Don’t come as some poet no one’s ever heard of.”

“Don’t worry, I will.” He turned, fingering the competition flyer in his pocket. A day and a half to write a love poem so unprecedented it would determine the course of his future. The thought made him quail with inadequacy. He walked on up a street that could have been anywhere, lined with convenience shops and run- down cafés: hardly the stuff of poetic inspiration. He was on the point of turning back when something caught his eye.

It was a Halloween display in a café window. It depicted a sack of coffee beans that was under attack from espresso cup vampires. The vampires had googly eyes and drawn-on pointy teeth, and they were swarming the poor beleaguered sack, spilling its blood in gushing coffee-bean rivers. The sack had distressed eyebrows and a mournful, gaping mouth. The overall effect was so charming that he caught his reflection smiling. He brushed his chronically messy hair aside and frowned, leaning closer. The Joe in the window didn’t look like the sort of person anyone would want to turn into a statue. He looked pasty, and dishevelled, and tired. Maybe a coffee would help.

He went inside. The café was cosy but shabby: the chairs, the tables, and indeed the entire structure appeared to be held together with duct tape. He edged past the bookshelves to the counter, where a girl with high cheekbones and warm dark brown skin was cleaning the espresso machine, her short braids swaying as she filled up the water tank. “With you in a second,” she said without looking.

“No bother, take your time.” He looked around: a couple holding hands across a table, a teenage girl frowning over her lap- top. No one was paying him the slightest bit of attention. He felt ashamed. Stupid to think the tour group had been following him. Rob was right: he was just a random undergraduate, of no interest to anyone.

“Sorry about that,” said the girl behind the counter. “What can I get—”

He turned round. For a moment, he was lost in her wide- spaced, deep brown eyes. Then he realised she was staring at him, and not in a way that suggested she was lost in his. She was wearing an expression of utter, consuming horror.

“You,” she said, like the universe was about to end and it was all his fault.

Excerpt. ©Catriona Silvey. Posted by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Giveaway: We’re giving away 3 copies of LOVE AND OTHER PARADOXES – enter today for a chance to win!

To enter Giveaway: Please complete the Rafflecopter form and post a comment to this Q: What did you think of the excerpt spotlighted here? Leave a comment with your thoughts on the book…

Meet the Author:

Catriona Silvey is the author of the international bestseller Meet Me in Another Life. She was born in Glasgow and grew up in Scotland and England. After collecting an unreasonable number of degrees from the universities of Cambridge, Chicago, and Edinburgh, she settled in Edinburgh where she lives with her husband and children.

erahime

What an interesting concept. Thanks for the except, HJ.

Mary Preston

What fun. I’d like to be part of a time traveling tour.

Diana Hardt

I liked the excerpt. It sounds like a really interesting book.

Nancy Jones

Enjoyed the excerpt.

debby236

Very intriguing – I think I would enjoy this book.

Rita Wray

I liked the excerpt. Sounds like a book I will enjoy reading.

Amy R

Sounds good

Daniel M

looks like a fun one

Mary C

Interesting.

cherierj

I enjoyed the excerpt. Sounds intriguing.

Patricia B.

An interesting concept and interesting excerpt. Joe and Rob are perfect roommates. Their banter in addition to Joe’s time at the library and introspection tell you much about him. The reaction of the girls makes the reader wonder what is going on and want to read more to find out.

Shannon Capelle

This a fun and interesting excerpt

Saundra McKenzie

Would love to win this book. Sounds good!

bn100

fun