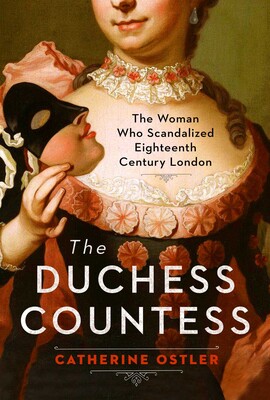

Today, HJ is pleased to share with you Catherine Ostler’s new release: The Duchess Countess: The Woman Who Scandalized Eighteenth-Century London

This “scintillating story superbly told” (The Times, London) explores the adventurous life of the stylish and scandalous Elizabeth Chudleigh, Duchess of Kingston—a woman whose infamous trial was bigger news in British society than the American War of Independence—and provides a clear-eyed and fascinating look into the sumptuous Georgian Era.

A clandestine, candlelit wedding to the young heir to an earldom, a second marriage to a duke, a lust for diamonds, and an electrifying appearance at a masquerade ball in a gossamer dress—it’s no wonder that Elizabeth’s eventual trial was a sensation. Charged with bigamy, an accusation she vehemently fought against, Elizabeth refused to submit to public humiliation and retire quietly.

“A superb, gripping, decadent, colorful biography that brings an extraordinary woman and a whole world blazingly to life” (Simon Sebag Montefiore, New York Times bestselling author), The Duchess Countess is perfect for fans of Bridgerton, Women of Means, and The Crown.

Enjoy an exclusive excerpt from The Duchess Countess: The Woman Who Scandalized Eighteenth-Century London

Chapter One: A Town of Palaces

In the first quarter of the eighteenth century, the London metropolis sprawls from the tar-caked wharves of Wapping in the east to the walls of Hyde Park in the west: the greatest, richest, most rapidly expanding trading city in the world.

St. Paul’s dominates the skyline in the City, as brick and stone rise from the ashes of the Great Fire. Mayfair is a neoclassical building site—the finest architectural period in England’s history is underway. Terraces of houses, church spires with glinting weather vanes are interspersed with swathes of parkland and open fields along the city’s artery, the salmon-rich silent highway, the Thames, which teems with sailing boats, pleasure boats, merchant ships, barges, small craft, and yachts.

A visitor in the summer of 1717 might witness the royal party, the new Hanoverian King George I and his attendants, on their stately barge, followed by an orchestra of fifty on another, playing Handel’s Water Music. They board at Whitechapel, pass marshes and heathland, and disembark at Chelsea, two miles upstream. The banks shine with beauty on either side of the river; it compares only to the river “Tyber… nothing in the world can imitate it.”1

Daniel Defoe calls London a “Great and Monstrous Thing,”2 but Chelsea is a village outside the city, an airy “town of palaces”3 where the river breeze shakes the boughs of the fertile gardens, none so spacious as those of the Royal Hospital.4 Prosperous townspeople head for Chelsea on Sundays for fresh, clean air. Here there are market gardens supplying fruit and vegetables for the town, alongside the graceful houses of noble families.5 At the hospital, the grounds are designed in French formal style, front and back; two L-shaped canals lined with swan houses flow from the river up the sweeping gardens. At the bank of the Thames, there is a terrace, pavilions, and steps down to the water. On the south side lies open country—trees, fields, homesteads, and windmills, like a scene painted by a Dutch old master. The river can only be crossed by ferry here and sheep are driven through the streets from local farms.

The austere redbrick splendor of Wren’s home for old soldiers contains a gracious three-story, high-ceilinged apartment in a river-facing wing. In 1726, this forms the light-filled London home of the lieutenant governor, Colonel Thomas Chudleigh, his wife Harriet, and the two children who have survived infancy: dutiful, seven-year-old Thomas and the angelic-looking, adored five-year-old Elizabeth. The hospital estate is their playground: they run along stone-flagged corridors and through colonnades of Doric columns under the inscription “IN SUBSIDIUM ET LEVAMEN, EMERITORUM SENIO, BELLOQUE FRACTORUM”I towards the chapel and the dining hall, past the gilded statue of founder Charles II cast as a Roman emperor, near-blinding when the sun hits it, and the royal portraits, across lawns lined with limes and chestnut trees, orchards, and their family kitchen garden, all the way down to the river.

The Chudleigh children grow up accustomed to a degree of stately grandeur and plenty. They have several playmates, the children of hospital staff—the secretary, the clerk of works, the physician6—and they live alongside the elderly majority, 400 old or wounded soldiers. Chelsea, like its inspiration, Louis XIV’s Hôtel des Invalides, is an architectural celebration of both military courage and a king’s benevolence. It is said that in England, the hospitals resemble palaces, and the palaces resemble prisons.7 Although the men sleep in small wooden berths and the stairs have shallow risers to aid their superannuated frames, prayers are said in the chapel beneath a glorious Resurrection by Sebastiano Ricci, and the Great Hall is fit for a medieval king. Governor Charles Churchill and Lt. Governor Chudleigh dine on a high table on a dais and the pensioners eat beneath them at long tables. Flags of battlefield triumph and portraits of princes line the walls, most prominently, Antonio Verrio’s mural of Charles II, crowned by the winged figure of Victory.

Within the institution live a chaplain, a porter, a baker, a brewer, an apothecary, a physician, a wardrobe keeper, linen-women, a sexton, cooks, butlers, gardeners, matrons, housekeepers, an organist, a barber, a treasurer, a canal keeper. The clerk of works oversees the building.8 Most senior of all the residents are the paymaster—in 1720, it was Robert Walpole, who became prime minister9 the following year—the governor, and the lieutenant governor.

As the children are aware as they weave their way through the faltering steps of the pensioners, with pats and smiles, the hospital is also a garrison, the men subject to military discipline: chapel twice a day, a roll call, and gate-closing time at 10 P.M. Some men—they are all men10—stand sentinel. A drumbeat calls them to the hall for lunch, between eleven and twelve. Food is served on pewter dishes; tablecloths reach to the floor, to double up as napkins; mugs of beer are poured from leather “jacks” or jugs, and the undercroft below the hall contains a brewery with six weeks’ supply.11 Pensioners wear variations of crimson cloth coats and tricorne hats, depending on rank and regiment. It is such a picturesque scene that tourists such as a young Benjamin FranklinII come to watch them from the gallery.

It is an idyllic place to grow up. The Chudleigh children’s earliest years are spent among the gracious architecture of this strange palace of military heroes, a compressed version of the strict hierarchy of Georgian society itself, with their father, a man of high status, respected by all.

Constant entertainment is provided by the river, which represents the chaotic world on the edge of the estate, a globe on the fringe of their consciousness. By the hospital stairsIII on the river, numbered, lightweight boats, painted red or green, wait on the water ready to take passengers: “oars” have two boatmen; “scullers” one. When a person approaches, the boatmen, dressed in velvet caps and red or green doublets, run to meet them, calling out “lustily ‘oars, oars!’ or ‘Sculler, sculler!’?” When the passenger chooses a boat, the others “unite in abusive language at the offending boatman.”12

The hospital is bookended by plutocrats’ villas, one the house of Lord Ranelagh, the late, corrupt hospital treasurer and army paymaster, to Swift, “the vainest old fool I ever saw.”13 Now lived in by his widow, its garden is known as the most resplendent in England, a “paradise”14 to Defoe. One day Elizabeth will frequent the same spot when it becomes the Ranelagh pleasure gardens, a lamplit land of nocturnal delight.

On the other side is the house of the Walpole family, with its octagonal riverside summerhouse topped with a golden pineapple, its Vanbrugh orangery, and its grotto. The Princess of Wales (the future queen, Caroline) and the court are frequent visitors, along with the ton,15 the fashionable set, such as the peripatetic writer Lady Mary Wortley Montagu,16 of whom we will hear more. Proximity to power is part of the climate.

Politics is discussed constantly in Chelsea. Writer, Whig Richard Steele (Col. Chudleigh subscribed to his entire Spectator when it was published in 1721) and scientist philosopher Isaac Newton meet at Don Saltero’s, the whimsical coffeehouse on nearby Cheyne Walk, where the cabinet of curiosities includes attractions such as a nun’s whip, “the Pope’s infallible candle,” and a bat with four ears.IV

The Botanick Gardens nearby with their cedar trees, the first in England, now belong to Saltero’s regular physician and naturalist Hans Sloane, whose collection of rare artifacts will one day become the British Museum.17

A child in this environment learns the importance of the monarch, military might, and courage. Young Elizabeth Chudleigh, with her expressive blue eyes, fair wavy hair, and the peachy plump cheeks inherited from her father, is armed with natural beauty and bravado. She has an intrepid, unconquerable spirit worthy of the military herself. She wears a simple bodice-and-skirt dress of pale calico, cap and apron, having graduated out of the padded infant “pudding” hat that protected her while she learned to walk. Her constant companion, her brother Thomas, now in breeches, wants to be a soldier like his father and the old war chroniclers who surround him with their stories. The Chelsea veterans of the Duke of Marlborough’s decisive battles against the French in Flanders and Germany18 dote on the children and their playmates, Horace Walpole, the prime minister’s son,19 diarist to be, a delicate child of eight, and Horace Mann, future diplomat in Florence, and his four younger siblings.

The hospital is a place of ritual, celebration, and pride. The children munch their way through the Ceremony of the Cheese at Christmas, where donated cheeses are cut and distributed; Restoration Day in May, when all wear oak leaves to commemorate Charles II hiding in the oak tree from Cromwell’s troops; and the Festival dinner for the reigning monarch, George I, when pensioners fire their muskets. They visit the Old Church, whose lonely spire dominates the river view on the north bank, and feast on piping-hot sugary buns from the nearby Chelsea Bun House, “a Zephyr in taste! As fragrant as honey,”20 which has royal custom and a cheerful queue.

As an indulged youngest child, Elizabeth is used to being the center of attention and is always at ease, fearless around men, especially, we can assume, military men.

Fifty years later, at her trial, Elizabeth proudly described the Chudleighs as “ancient, not ignoble”; the women “distinguished for their virtue,” the men “for their valour.”21 Family was always important to Elizabeth, partly because she was a Chudleigh twice over: her parents were first cousins. The name itself was of profound significance to her. By the time she died, she had convinced two monarchs—Louis XVI and Catherine the Great—to let her rename two estates in countries hundreds of miles apart Chudleigh, and attempted to coerce heirs into changing their names to that of her waning tribe.

Some of the brave Chudleighs were as reckless as they were adventurous. Although one naval officer “distinguished himself” against the Spanish Armada, another, John “Chidley,” a privateer who had sailed with his Devon kinsman Walter Raleigh in the search for El Dorado,22 sold his estate for an expedition and died in the Strait of Magellan, losing his investors’ money along with his own. Others were sheriffs, lawyers, and men who—a notable family characteristic—made advantageous marriages. In the English Civil War, a George Chudleigh raised the family to a baronetcy when he swapped allegiance from Parliament to king.23

Less was said of other ancestors, such as Elizabeth’s maternal great-grandfather Sir Richard Strode, an MP from the Devon gentry, “a man of unquiet spirit and contentious nature”24 who was incarcerated in Fleet Prison for debt and became mentally unstable. Or of Henry VIII’s wily minister Thomas Cromwell, eventually executed for treason, of whom she was also a direct descendant. Ambition sometimes blighted reason.

Many centuries earlier, marriage had brought into the family her father’s childhood home, a woodland manor house and estate near Higher Ashton, in a river valley ten miles from Exeter. Elizabeth’s grandfather Sir George, 3rd Baronet, was a man of books and a landowner. Yet for all the male forbears, Elizabeth Chudleigh’s most remarkable ancestor was a woman. Her grandmother Lady Mary Chudleigh was an early pioneer of independent female thought, in spite of the fact that she lived an isolated life among the remote rural backwaters of Devon, a week’s carriage ride from the cultural center of the metropolis. She was a proto-feminist composer of lyrics, verses, essays, tragedies, satires, and operas. Sloe-eyed, dark-haired, witty, and opinionated, she was a friend of Dryden,25 who asked her opinion on his works. Her best-known poem, “The Ladies’ Defense,” is a riposte in rhyming couplets to a sermon on marriage, “The Bride-Woman’s Counsellor,”V in which women, who have “weaker capacities to learn than men” were advised that “the love of a husband very much does depend on the obedience of a wife.” Mary wrote in retort: “Wife and servant are the same/ But only differ in the name.”

Mary was one of only two published female poets in the first decade of the eighteenth century.26 Her family were Puritan thinkers and she corresponded with a circle—the poet Elizabeth Thomas, “the first English feminist”27 Mary Astell, the Rev. John Norris—who believed in women’s intellectual autonomy.

She achieved her writerly success in spite of ill health and much bereavement: of her six children, only two, George and Elizabeth’s father, Thomas, survived into adulthood. A devout Anglican and royalist, she dedicated one book to the Electress Sophia of Hanover, the cerebral woman who would have succeeded Queen Anne if she had lived three months longer, and another poem to Anne herself, after the death of her son, the Duke of Gloucester, at the age of eleven. Mary’s “Ode to the young Duke of Gloucester” was written from one heartbroken mother to another:

His Face was Charming, and his Make Divine

As if in him assembl’d did combine

The num’rous Graces of his Royal Line.

Lady Mary was much admired—one contemporary writer said she was the “Glory of her Sex and the Ornament of her Country.”28 Her sons must have been brought up with the peculiar idea that women’s mental prowess, their dignity, was somehow equal to men’s, their emotional life something to be expressed, not buried.

The elder George would lead a quietly opulent upper-class life in the country, while the younger Thomas, Elizabeth’s father, fought his way to a position as an accomplished courtier and soldier. He was born in 1687, a year before the Glorious Revolution that secured the Protestant succession. As his brother was the heir, his father bought him an army commission when he was a child.29 In May 1702, the expansion of the War of the Spanish Succession meant that the new queen, Anne, had to raise an army.30 Charles II, the Hapsburg King of Spain, had died childless and as his closest heirs were either an Austrian Hapsburg or a French Bourbon, the succession threatened the delicate balance of power in Europe. The English Parliament was united in wanting to thwart French supremacy. In December, when he had just turned fifteen, Thomas became second lieutenant in a new regiment of marines,31 and was promoted to captain five years later.32

The War of the Spanish Succession saw over a decade of murderous belligerence waged across Europe with resolute John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, at the fore. Chudleigh was among that daunting “scarlet caterpillar, upon which all eyes were once fixed, [that] began to crawl steadfastly day by day across the map of Europe, dragging the whole war with it.”33 He served “with reputation”34 in the march through Flanders, “from the ocean to the Danube,” passing impregnable lines, laying siege to fortresses, and prompting surrenders under Marlborough.

The Chudleighs were related to the Churchills, another Devon family: John Churchill’s uncle had married a Strode, Harriet’s mother’s line, and they therefore considered each other cousins. Marlborough’s nephew, Charles Churchill, was governor of the Royal Hospital when Elizabeth was born. The duke was England’s great Royal military hero, and even after her husband’s death in 1722, the duchess was its alternative queen. With her boundless influence, one contemporary branded her “the evil genius of the whole state.”35

The connection was a tangible advantage. Marlborough wrote to Robert Walpole, then secretary of war, in 1709 angling for him to ask the queen to promote Chudleigh,36 who was rewarded for his “meritorious conduct” in November 1711 with a lieutenant colonelcy,37 and in November 1712, days before his marriage, the queen gave him the colonelcy of his own regiment, Chudleigh’s Regiment of Foot. This regiment was a colorful and dashing sight, the uniform a “tri-corned hat, a full-skirted scarlet coat, turned up with brightest yellow facings, a scarlet waistcoat, white trimmings and white gaiters.”38

Army life meant periods of intense, heroic activity interspersed with expensive, alcohol-sodden inaction. After war ended in 1713, the regiment dispersed, to be reformed by Colonel Chudleigh in the summer of 1715, when George I arrived from Hanover and the Old PretenderVI reignited his mission to reclaim the crown for the Catholics.39 In the autumn of 1719, Elizabeth’s father fought in Spain in the Vigo Expedition, with his regiment seizing seven ships, settlements, and arms waiting for the Pretender. They returned victorious and the King of Spain pressed for peace.

On January 14, 1715, while his regiment was out of service, Chudleigh also became the lieutenant governor of the Royal Hospital at Chelsea, a role that included intermittently supervising the Plymouth garrison.VII At twenty-seven, he was young for the position, but the appointment was in the gift of the queen, with whom he had ties through the Marlboroughs and his parents-in-law.40 The lieutenant governor was responsible for the day-to-day running of the Royal Hospital. In this nepotistic era, it meant he had grace-and-favor accommodation and two salaries, and one when his regiment was not required. Chudleigh was companionable, hearty, and fond of brandy.41 A 1715 portrait shows a charmingly chubby-cheeked, affable-looking fellow with bountiful curly hair, a double chin, an epicurean dressed in full armor topped off with a lace cravat. He exudes bonhomie, a quality his daughter would inherit.

He had not looked far for a bride: in 1712, he married his first cousin Henrietta Chudleigh, known as Harriet. She was a child of the court: her father, Hugh Chudleigh, younger brother of Thomas’s father,42 had been Marlborough’s adjutant in the army, and later became Queen Anne’s commissioner of the Master of the Horse,43 and her mother Susannah was the courtier who alerted the Duchess of Marlborough—herself a former maid of honour44—to the plight of their mutual relation, Abigail Hill,45 who then supplanted the duchess as royal favorite.46 The Marlborough allegiance was of such importance to the family that in 1717, when Colonel Thomas and Harriet Chudleigh entertained the duke and duchess at dinner at Chelsea, they fanfared the occasion in the press.47

As Whig followers of Marlborough, the wider Chudleigh family was staunchly loyal to the Hanovers. Both of Harriet’s brothers, George and John—the latter, a former page to Anne’s husband, had once killed a man in a duel48—and her brother-in-law William Hanmer were in the same regiment, the aristocratic Coldstream Guards, under the Earl of Scarborough. All became colonels.

Yet as the family rose, Thomas and Harriet’s financial affairs remained stubbornly precarious. In 1719, Colonel Chudleigh’s father died and left him £1,000 and the minor Hall estate in Devon.49 The bulk of the family fortune went to the elder son, George. Harriet had had a middling £1,500 dowry, and she and her husband were not well-off by the standards of their class.50 And they—along with the whole country—were in for a brutal shock. In 1720, the South Sea Company, established to provide funds for the national debt built up by warfare, had become a bubble that was about to burst. Neither the hospital itself, which had invested in the stock,51 nor Elizabeth’s parents would escape the feverish gold rush unscathed. Colonel Chudleigh had sunk his entire cash inheritance into the South Sea Company.52

Like her mother-in-law, Harriet was weighed down by numerous pregnancies and the devastation of infant mortality. Four of her children died within months of their birth. Only two survived: Thomas, born June 9, 1718,VIII and Elizabeth, born March 8, 1721, baptized on March 27, at St. Martin-in-the-Fields. After the South Sea Bubble, the two Chudleigh children would have to make their own way.

Advancement in eighteenth-century England meant reliance on networks and tribal support. The Chudleighs were royalists, Whigs, military, a Chelsea family, and a Devonian one; an interdependent web of connected families, kin, and allegiances.

Such a matrix would prove crucial. Elizabeth’s father sold his army commission in 1723—either through ill health, financial need, or a desire never to leave Chelsea and his children again. Three years later, in the cold, damp spring of 1726, he fell sick at Chelsea. In spite of having Chelsea’s whole medical team at his disposal, he could not be saved.

He died, on April 14, at the age of thirty-eight.

Before Elizabeth’s sixth birthday, the blithe surroundings of her riverside infancy were gone, all security and serenity lost. Nothing was to be quite straightforward for Elizabeth ever again.

I. “For the succour and relief of veterans, broken by age and war.”

II. In 1725, when the founding father was a trainee printer in London. He swam back down the Thames from Chelsea to Blackfriars.

III. Stairs: a flight of steps down to the water, which led to a stop for watermen to pick up passengers at high tide. Often situated next to a pub.

IV. Also: “21 Petrified crab from China; 27 The Worm that eats into the Piles in Holland; 31 A piece of rotten wood not to be consumed by fire; 67 A pair of Nun’s stockings; 76 A little Lobster; 102 A curious snuffbox, adorn’d with ivory figures; 119 the Hand of an Egyptian Mummy; 135 An Ostrich’s Leg; 142 A Cat of Mountain; 302 A Whale’s pizzle.” From A Catalogue of the Rarities to be seen at Don Saltero’s Coffee-House in Chelsea (1729).

V. The sermon was made by the Rev. John Sprint at a wedding in Dorset, on May 11, 1699.

VI. The “Old Pretender,” James Francis Edward Stuart, son of James II of England and VII of Scotland: the first of the fifty-seven Catholics who could claim the British throne by bloodline ahead of George I.

VII. In times of conflict, the Chelsea Corps of Invalids was drafted back into the army to defend a garrison, in order to free up the regiment for foreign service.

VIII. Baptized June 23, 1718, at Chelsea.

***

Excerpted from The Duchess Countess published by Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2022 by Catherine Ostler.

Excerpt. ©Catherine Ostler. Posted by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Giveaway: Hardcover copy of The Duchess Countess, US only

To enter Giveaway: Please complete the Rafflecopter form and post a comment to this Q: What did you think of the excerpt spotlighted here? Leave a comment with your thoughts on the book…

Meet the Author:

Catherine Ostler is an author and journalist who has been editor-in-chief of Tatler, the Evening Standard (London), and editor of The Times (London) Weekend Edition. She has also written for a wide range of publications, including Vogue, Daily Mail (London), and Newsweek. She read English at Oxford University, specializing in literature.

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Duchess-Countess/Catherine-Ostler/9781982179731

EC

The excerpt provided is profusely appreciated. Thanks, HJ!

Amy R

Sounds good

Dianne Casey

I really enjoyed the excerpt from the book. Would really love to read the book.

Patricia B.

Definitely an interesting look inside English society. It sounds like we will get a much more complete view of the maneuverings behind the scenes to maintain connections, status, wealth, and appearances than we usually do. Thank you for the interesting excerpt.

Debra Guyette

Thanks for the wonderful excerpt/ I am interested in reading more.

Lori Byrd

sounds so good.

Janine

I enjoyed the excerpt. Thank you!

Jana Leah

I’m looking forward to reading more.

bn100

interesting

Texas Book Lover

This sounds really interesting!!!

Daniel M

looks like a fun one

Teresa Williams

Sounds wonderful .Want to read more.

Charlotte Litton

Sounds good

Bonnie

What an interesting book! Great excerpt. I’d love to read more.

Terrill R.

I’m absolutely intrigued by Elizabeth Chudleigh’s life. I love real historical figures in my books and this woman sounds fascinating.