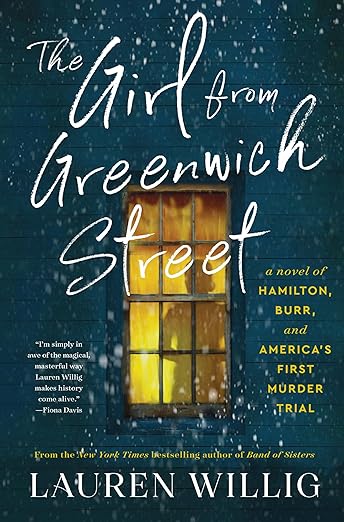

Today, HJ is pleased to share with you Lauren Willig’s new release: The Girl from Greenwich Street

Based on the true story of a famous trial, this novel is Law and Order: 1800, as Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr investigate the shocking murder of a young woman who everyone—and no one—seemed to know.

Just before Christmas 1799, Elma Sands slips out of her Quaker cousin’s boarding house—and doesn’t come home. Has she eloped? Run away? No one knows—until her body appears in the Manhattan Well.

Her family insists they know who killed her. Handbills circulate around the city accusing a carpenter named Levi Weeks of seducing and murdering Elma.

But privately, quietly, Levi’s wealthy brother calls in a special favor….

Aaron Burr’s legal practice can’t finance both his expensive tastes and his ambition to win the 1800 New York elections. To defend Levi Weeks is a double win: a hefty fee plus a chance to grab headlines.

Alexander Hamilton has his own political aspirations; he isn’t going to let Burr monopolize the public’s attention. If Burr is defending Levi Weeks, then Hamilton will too. As the trial and the election draw near, Burr and Hamilton race against time to save a man’s life—and destroy each other.

Part murder mystery, part thriller, part true crime, The Girl From Greenwich Street revisits a dark corner of history—with a surprising twist ending that reveals the true story of the woman at the center of the tale.

Enjoy an exclusive excerpt from The Girl from Greenwich Street

Prologue

The deceased was a young girl, who till her fatal acquaintance with the

prisoner, was virtuous and modest. . . .

—William Coleman, Report of the Trial of Levi WeeksNew York City

December 22, 1799

The shadows were gathering in the back of the house in Greenwich Street.It had been one of those clear, bright winter days, when the sun shone pitiless as the Last Judgment, all light without warmth, but the early winter dusk was finally falling. Elma welcomed it, even if it did make it hard to see her reflection in the scrap of mirror Caty had allowed was permissible to make Elma neat and tidy.

Elma draped a kerchief across her bodice, studying the effect of the fichu. Whatever she did, her calico gown and dimity petticoat looked decidedly provincial. There was only so much one could do with old patterns, cheap fabrics, and a Quaker cousin with an eye for propriety.

Soon. Soon she’d have dresses of fine muslin and gauze, embroidered all about with this season’s whimsies; she’d have clocked stockings of sheerest silk, and shawls so fine one could draw them through a ring. Oh, and she’d have the rings too, starting with one tonight. He’d not

shown it to her; he wouldn’t. Let it be a surprise, he’d said, a surprise for their wedding night. Surely he should be allowed some surprises.

She’d surprises of her own, Elma had countered, trying to sound like the lady of the world she meant to become, not the poor cousin from Cornwall, New York, everyone’s drudge and morality tale.

She’d taken his hand in hers and kissed each finger, one by one, her eyes on his all the while.

He’d liked it well enough, she could tell, because his breath had quickened, and he’d nodded and said a quick, “Tonight,” before a step on the stair behind them signaled—

“Elma?”

The kerchief slipped from Elma’s grasp at the sound of Caty’s voice, so rudely intruding into her own private place.

Elma took her time retrieving the kerchief. “Did you want me?”

“No. . . . That is . . .” Caty hovered at the threshold, neither in nor out. Caty was never still: always up and down the stairs, in and out, seeing what needed doing; seeing who wasn’t doing what they were meant to be doing.

Watching. Always watching. Pretending concern. Oh, Elma, thee will take a chill. Let me give thee a kerchief. Stuffing thick fabric into the neckline of her dress, muffling her in shawls. She’d like to muffle Elma out of existence, Elma had no doubt. The family embarrassment.

Somewhere, far to the south, in Charleston, Elma’s father lived with his other family. Elma used to dream he would come and sweep her away, dress her in silks and laces, put her at his right hand. My daughter, he’d call her.

For all she knew he had other daughters. He’d had another family already, that’s what Elma’s uncle David said. A sinner leading Elma’s mother like a brand to the burning. Twenty-three years Elma’s mother had been burning, acknowledging and acknowledging and acknowledging her sin, but never any closer to salvation.

Elma’s mother had been sixteen when she’d fallen from grace with a soldier in the Continental Army. Six years younger than Elma was now.

Elma was older and she knew better. If Elma were to burn, she’d made up her mind to do it in grand style.

“Which do you like?” Elma held up two handkerchiefs, alternating them against her bodice to show the effect. “This one? Or that one?”

A furrow appeared between Caty’s pale brows. “The second kerchief—is that Peggy’s?”

Elma shrugged. “Peggy will never mind. Besides, I don’t mean to mop my nose with it. She’ll have it back none the worse for wear.”

By then Elma would have finery of her own, a doting husband to shower her with the niceties of life, not clothe her in calico and set her to drudge like Caty: minding the children, boiling the linens, feeding the boarders, trimming hats in the millinery that supplemented the

income of the boardinghouse.

Caty hesitated, and Elma could see her struggling with the desire to read Elma a lecture on coveting thy neighbor’s kerchief. Easy enough to divide between mine and thine when one had something of one’s own. Elma’s entire life had been pieced together like a quilt from scraps

begged from others. If there was one thing she’d learned, it was that it was better to take than to beg.

“Thy fichu is crooked,” said Caty at long last, and Elma knew she’d won. Caty crossed the narrow room, beneath the slope of the gambrel roof, and with sure fingers tugged the fichu into place, tucking it into Elma’s bodice, higher than Elma liked. “Thee are determined to go out

tonight?”

Like the good Quaker she was, Caty minded her thees and thous.

“It’s a fair, fine night.” Elma deliberately misunderstood her.

Caty’s fingers hesitated on the linen. “After thy illness. Should thee take a chill . . .”

“Why, you would nurse me back to health. As you did before.” Elma looked hard at the top of Caty’s bent head, daring her to look up and meet her eyes. “Just as you did before.”

“Tonight . . .” Caty took a step back, her work-reddened hands clasping and unclasping, unaccustomed to emptiness. “Hope told me. She told me thee mean to be married.”

“It’s a fine thing when one’s family won’t keep a confidence.” Elma felt a curious sense of elation. She’d known Hope would never be able to resist telling Caty; Hope would be bursting with it, all self-righteous good intentions. And jealousy. Mostly jealousy, made worse by having to cloak it in virtue.

“You—thee—ought to have told me.”

Oh ho, Caty was flustered if she was falling into secular ways, saying you instead of thee.

“Why? So you could make me my bridal clothes?”

“Thy family—” began Caty, and faltered.

The steps outside creaked and they both jerked toward the door. It was a heavy tread, not Hope’s light step or Peg’s cheerful bounce. Elma retreated behind the curtain of the bed.

“Where’s Elma?” It was Levi’s voice, a deep, cheerful baritone. Elma felt her breath release, raising a faint cloud in the cold air.

“She is hid behind the bed.” There was no need for Caty to sound so prim about it.

Elma stepped out from behind the curtain. Levi smiled in relief at the sight of her, and she was struck, as always, by the vitality of his presence, the simple, uncomplicated joy. She loved him and hated him for it.

He limped forward, favoring the leg he’d bruised at his brother’s timber yard that morning. Elma had plastered it herself, sponging the blood and giving him a good scolding. “Don’t mind me. I want you to tie my hair.”

“Couldn’t your apprentice do that?” Elma took the black ribbon he held out to her, as he turned his back, bending his knees to make himself shorter. His light brown hair was loose around his shoulders, untouched by powder. She gathered it into a queue.

“And have me in knots? You’ve a gentler touch.” He cast a glance over his shoulder at her, inadvertently pulling his own hair. “Ouch.”

“Stay still and you won’t hurt yourself.” Elma could see Caty’s eyes going from one to the other of them. Elma hastily tied the ribbon, giving Levi a light push. “There. You’re fit for company. Now go away and leave us be.”

He looked at Caty, and then at Elma. Elma gave him a slight shake of her head. He took it in good grace. Levi took everything in good grace. He’d never been out of grace, couldn’t imagine what it was like. “As you command.”

His steps creaked away, up the stairs, to his own room on the third floor.

When Caty was away in September, Elma had stayed in the big room in the front on the second floor, right below Levi’s.

But that had been in the last blazing of the summer heat, when the sun burned off the sidewalks, and those who could afford it fled the yellow fever, piling into boats and wagons, off along the Hudson. The world had felt overripe, everything set to burst; one had to grab while one could, while one was alive, while the fruit hung heavy on the trees, abandoned in

the half-empty city. What was one to do but pick what one could?

But that was September. The yellow fever had gone; the wagons with their coffins rattling to the graveyard had been replaced with the sound of carriages bringing home the lucky ones who had escaped to the country. The acrid scent of the gunpowder from the cannons fired to drive off the sickness had faded, the tang of the sea blowing again through her window with the cooler air, with just a hint of the stench of the glue manufactory when the wind was in the wrong direction. There were knockers put back on doors, businesses reopened, and life went back to the way it was. Caty, Hope, and the children came home from Cornwall. And Elma retreated to this dark chamber in the back of the house where the shadows fell early and the small windows caught no light.

There were times Elma could scarcely remember the girl she’d been in September, the dreams she’d dreamed in that big front room. When the trees blazed red and gold, one last burst of wonder before the fall.

Now all was gray and sharp with frost. What she did tonight wasn’t for passion, but for cold, hard sense. She’d learned her mother’s lesson and her own.

Caty looked meaningfully at Elma. “Levi seems in good spirits.”

“Yes,” said Elma, not trusting herself to say more.

“I had thought, with his leg, he might not be fit to go out tonight.”

“It was only a scratch, hardly worth the fuss.” Any elation she might have felt was gone. It was no fun taunting Caty. Not now. Elma just wanted to be left alone. Tonight, she’d leave this room, leave it for good. Down the stairs, out the door, to the meeting place in Lispenard’s Meadow. She was making the right decision, she was.

But the game of teasing Caty had lost its savor.

From downstairs came the wail of a child, Caty’s youngest, one and a half years old. Caty looked distractedly toward the stairs, clearly torn. “Thee promise to keep warm?”

“Oh, we shall.” It was too easy to make Caty blush, even after four children.

Caty took refuge in the petty details in which she delighted. “Thy hands—those mittens will scarce keep thee warm. Thee ought to have a muff, to keep off the chill. Elizabeth next door . . . I might borrow it for thee.”

“There’s no need to fuss,” said Elma.

“Catherine! Where are thee?” A masculine voice bellowed up the stairs, in tune with the baby’s wail: Caty’s husband, Elias, home from Sunday services.

“Back from meeting already?” Elma could see Caty’s mind revolving like the clock in Mr. Baker’s Museum, all wheels and gears, checking all the tasks done and undone, tea to be got, children to be minded, boarders to be fed, her husband to mollify, her unwanted cousin to be speeded on her elopement—but with warm hands, a sop to Caty’s conscience.

“Catherine!” Elias’s voice was high-pitched, querulous. Elma could

hear the stomp of booted feet on the stairs, as the sound of the baby’s howling grew louder. “The baby wants fixing!”

“Presently!” Caty called. She turned back to Elma. “Thy cheeks—they have turned so pale. If thee be frightened . . . He’s a good man, Levi. I shouldn’t think . . .”

“I’m not frightened. I’m just cold.” Elma moved quickly to the door. “You’re right. I’ll get the muff from Beth.”

Caty trailed after her, a furrow beneath the plain white line of her cap. “Thou will remember to return it? The muff?”

“If I don’t, I have no doubt you’ll remind me.”

Caty was good at that. She was good at reminding Elma that this wasn’t her house, these weren’t her things; everything she had, she had on sufferance.

It didn’t matter now, Elma told herself. It didn’t matter. None of it mattered.

Caty could keep her dull house and her dull husband and her runny-nosed children. Elma would be a great lady, like Mrs. Church. Her lover had promised that she’d sweep through town in a coach and four, with plumes in her hair and jewels on her heels. No Quaker meetinghouse for her. She’d attend church at Trinity, in a pelisse tailored in Paris and her head modestly bent over a calfskin hymnbook.

Perhaps she’d come back from time to time, and let the children marvel at her, at her soft, scented skin and her soft, scented silks, at the rustle of her petticoats and the curve of her curls.

Yes, Elma rather liked the thought of that.

Let them know the brand from the burning might be a phoenix in disguise, ready to blaze far above them.

Averting her face, avoiding Elias and the howling child, Elma hurried down the stairs, through the sounds of the boardinghouse—the children shouting, the baby fretting, Caty bustling, journeymen laughing—letting herself out into the crisp, smoky December air. The street was busy with people paying Sunday calls, ironmongers and tobacconists, builders and grocers, bundled against the chill, dodging out of the way of the sleighs that jangled down the center of the street.

She wouldn’t miss it, any of it, Elma told herself.

To the south, above the close-crowded wooden houses, Elma could see the spire of Trinity Church on Broadway, where the houses were of brick, not wood; where the women wore silk from the ships whose masts pocked the sky; where she would have a home of her own where the beds weren’t rented out by the week.

Or perhaps they’d board one of those ships out there in the harbor and sail away to a real city, to London. What was New York, after all? Just a jumble of houses carved out of mud and meadow, filled with the refuse of the world.

Like her.

“Elma!” The ironmonger’s sixteen-year-old daughter, Fanny, waved

wildly at her from the neighboring stoop.

Pretending not to hear, Elma turned sharply to her left, toward Beth Osborn’s house, to borrow a muff to wear to her wedding.Chapter One

On Thursday last was found in a well dug by the Manhattan Company, on the north side of the Collect (but which afterwards proved useless) the body of Miss G. E. Sands who had been missing from the evening of Sunday the 22nd.

—Greenleaf’s New Daily Advertiser, January 8, 1800New York City

January 6, 1800“I heard they found her muff floating in a drain in Bayard’s Lane.”

“No—not a drain. The Manhattan Well.”

Greenwich Street heaved with people, shoving, pushing, jostling.

Alexander Hamilton slowed, contemplating this unexpected hindrance. His two clerks had been more than usually slow and doltish this morning, his correspondence more than usually irritating, so he had darted out of his office with the object of buying Eliza a coffee biggin. She’d looked so heavy-eyed at the breakfast table, bouncing baby Betsy in one arm while presiding over the coffeepot with the other. The coffee biggin, Gouverneur Morris assured him, produced a superior, stronger quality of coffee. Whether it did or not, Alexander had no idea, but it would be something to offer Eliza, to take that smudged, hollow look from her eyes.

Soon, he’d promised her. Soon he’d step away from public life. They’d build an idyll in the countryside, near enough to town that they could enjoy the society of their friends and he could lend his aid as needed to his fellow Federalists, consult on the odd legal matter. . . . Soon. But General Washington had entrusted him with the organization of the new army—never mind how President Adams resented it, how he worked to undermine all of Alexander’s plans—and

with the general in his grave this past month, Alexander felt more keenly than ever how strongly he needed to press the work forward.

Then there was the petty manner of money. Money, always money. Money for the children’s schooling; money to build their house in the country. Money to be earned from the legal practice that was suffering sorely as Alexander struggled to build an army that he knew was needed, if only the ignoramuses in Philadelphia could just be brought to see it.

Just a bit longer. A bit longer and he’d be able to move Eliza and their brood to the countryside, and live the life of a country squire, going out with his fowling piece to shoot ducks in the morning mist, his Eliza presiding clear-eyed at their own tea table. Soon. Eventually. Someday.

But for now, he could buy her a coffee biggin.

Or so he’d intended. Greenwich Street was impassable with this inexplicable crowd. Unlike the elegant brick homes lining Broadway, the houses here were of wood, ugly, clumsy structures so newly built that Alexander could practically smell the wood shavings and fresh-mixed plaster. It was a tinderbox of a street, but it wasn’t a fire causing this unaccustomed press of people; he would have smelled the smoke before this.

Only a block away, the students of his alma mater, King’s College—now Columbia—rushed to class in their flapping gowns, but this didn’t have the flavor of a student riot; there wasn’t enough Latin being spoken. Besides, the students were enclosed behind the high gates of the college, effectively locking them away from the city around them. When Alexander was in college, there’d been much made of the college’s proximity to the so-called Holy Ground, where pleasure could be found for a price and brawls sometimes broke out between customers and madams, or madams and enraged moralists.

But that was on the other side of the college. This was a street of respectable small tradesmen, running their businesses out of the front rooms of their homes: grocers and tobacconists and, most important, an ironmonger who was reputed to make excellent coffee biggins. Alexander could just make out the wooden sign creaking from one of the awnings, right at what seemed to be the epicenter of the excited crowd.

It seemed unlikely that half the city had experienced a simultaneous desire for a coffee biggin.

“Alexander!” A hand clapped him on the shoulder, and Alexander looked up into the face of his old friend and colleague Richard Harison, once his partner in law practice, still his partner in politics. “Or should I say Major General?”

“Never among friends.” Or possibly not at all if that ass Adams had anything to do with it, not to mention Aaron Burr and his Republican rabble, downplaying the threat from France, ignoring the dangers of a Revolutionary regime untrammeled, agitating for the disbandment of Alexander’s army. The United States Army, that was, or would be, if Alexander was given the supplies and support he so desperately needed.

“How goes the business of the army?”

“Busily,” Alexander quipped.

Even to an ally like Harison, Alexander could never admit the fear that it was all for naught, all his preparations and plans, the punishing pace he had set himself and his clerks. That ass Adams had never wanted the army and he’d certainly never wanted Alexander. Alexander had been forced on him, by the one person with the power to do so. The person who had lain cold and still in his grave these past three weeks. Alexander had marched in General Washington’s funeral procession; he’d listened to Gouverneur Morris deliver the funeral oration; but he still couldn’t quite entirely believe he was gone, that great man who had loved him as his own father never had.

And there was his Eliza with gray in her dark hair, their Philip studying at King’s College—not King’s anymore, but Columbia—and Harison, who had been in his prime when they had begun their practice together just after the war, now heavy-jowled, the new Brutus hairstyle not hiding the fact that his hair was thinning at the temples, and gray now, entirely gray.

How had they come to this? This wasn’t what Alexander had thought his middle age would be, scrabbling after pennies, after favor, after political advancement, surrounded by incompetents and opportunists.

Alexander cleared his throat. “What ruckus is this? Are the apprentices revolting again?”

“The apprentices are always revolting.” Harison chuckled at his own tired sally. “You must have heard, surely? About the girl. The girl in the well.”

The man in front of him had said something about the Manhattan Well, that misbegotten monstrosity. “Ah,” said Alexander, as if he knew more than he did. “Are all these people—”

“Here to view the corpse.” Harison shoved his hands in his waistcoat to warm them. “You haven’t come to gawp at the girl in the well, have you?”

“I haven’t. I came to find a coffee biggin for Eliza. The baby is cutting her teeth,” Alexander added.

“Did you try brandy—”

“Rubbed on her gums? Or for ourselves?”

“Either.” Harison grimaced in sympathy.

“Neither had the least effect, I regret to say. Poor Eliza has had no peace. And neither have I.”

“Cherish it. Cherish her.” Harison’s face drooped like melting candle wax. He was, Alexander knew, thinking of the much younger wife he’d adored, his Fanny, gone two years now, leaving Harison with their four young children. Alexander couldn’t imagine such a future, an existence without Eliza. She was the still center of an ever-moving world. “The time—it goes faster than you know.”

“I’ve promised Eliza to spend more time at home—as time allows.”

“Time—or your ambitions?”

That was the trouble with old friends. They felt comfortable asking awkward questions. “You haven’t come for the girl in the well, have you?”

“I’ve come as an officer of the court,” Harison said grandly. “And, I admit, out of a certain measure of curiosity. The family’s allowing the public in to see the body—fanning

the flames. If I’m to sit on the case, I feel it’s my duty to see what every other man jack in the city will have seen.”

“That’s what they’re all waiting for? To see the girl’s corpse? It’s macabre—barbaric.”

“It’s human nature,” said Harison equably.

“Of the basest sort.”

“It makes a compelling story,” said Harison thoughtfully. “Perhaps because it’s such a familiar one. The girl lured . . . seduced . . . discarded. And she’s a Quaker, to boot. You haven’t read of it in the papers?”

Alexander had been avoiding the papers because the papers refused to avoid him. He’d promised Eliza he’d hold his fire, but it was hard when Republican scandal sheets slandered him and his fingers itched to take up his pen and defend himself.

Like last time. And they all knew how that had gone. Mercifully, Harison was still going on about the girl in the well. “It’s the talk of the town. There are already tales of hauntings. The girl’s tormented soul begging justice, all that sort of nonsense. People half expect to see the sheeted dead squeaking and gibbering in the street. You’d know nothing about that.”

Harison looked pointedly at Alexander, who had gotten in trouble, last year, over a prank involving a supposed ghost.

More fodder for the papers. A man couldn’t arrange a joke with his family without being splattered with ink.

“Have they arrested anyone for the crime?” Alexander asked abruptly.

“Levi Weeks. He’s a young carpenter who boarded in the same house. They’re saying he got her with child and killed her to keep from marrying her. You’ll have heard of his brother—Ezra. He laid the pipes for the Manhattan Well.”

That well, that blasted well again. Alexander seethed at the thought of it. Burr had hoodwinked him; he’d hoodwinked all of them. And the worst of it? He’d had Alexander fighting for his Manhattan Company, supposedly formed for the purpose of digging that well, among others. A well to bring clean water to the city, to fight the dreaded scourge of yellow fever. What civic-minded soul wouldn’t support that project? Alexander had drafted the proposal, crafted the clauses, sweated ink and effort over it. Not a party matter, Burr had promised him, and offered him seats on the board for Federalists, including one for Alexander’s brother-in-law John Church, proof that this was an undertaking meant to benefit the whole.

Except it wasn’t.

The well was only a ruse. In the last hours before the bill went up for vote, Burr had inserted another clause, one setting up a financial institution. It wasn’t a well he was proposing but a bank, a bank to rival Alexander’s own Bank of the United States.

And he’d done it. With Alexander’s support.

How Burr must have laughed at him in his mansion, Richmond Hill. How all the Republicans must have chortled to see Hamilton throw his support behind a measure designed to unman him.

Alexander burned at the very thought of it, but there was nothing he could do now. The bill to establish the Manhattan Company had passed—thanks to Alexander’s efforts. The Manhattan Company was at this very moment amassing funds and extending credit, a monstrous

instrument that pretended to the public good while serving private gain.

For Burr, all for Burr. And the Republican Party.

Harison was still talking. “Young Colden will prosecute, of course. Weeks has retained Brockholst Livingston for his brother’s defense. And Colonel Burr.”

“They’ve hired Burr for the defense?” How Burr would enjoy that, posturing in the courtroom in his sleek black frock coat.

He’d have Livingston do the work while he took all the credit. It would play directly to his claim to be the champion of the working man, a vivid image for voters to take with them to the polls: Burr using his eloquence to save a lowly carpenter from the gallows.

Unless . . . A germ of an idea began to form. “What evidence is there against the young man?”

“Precious little, as yet. Rumor and hearsay—the sentiment of the street. They’ve been baying for his blood. Someone’s been handing out broadsides, riling them up. The mob’s convinced he did it. They’ll settle for nothing less than his neck in a noose.”

“That’s not justice. That’s lynch law.” Charles Lynch and the men like him who took it upon themselves to enact vengeance on those they’d condemned without process of law were anathema to everything Alexander stood for. That wasn’t the sort of polity he’d fought for, with the sword and with the pen. “What makes them think it was this young man?”

“The family claim he was walking out with her—they’ve been quite voluble about it.”

“Did anyone else confirm that? Were they seen together? Is there any evidence the girl was with child?”

“You sound as though you’re taking down the points of the case.” When Alexander didn’t reply, his friend looked at him sharply. “You’re not, are you? Weeks is well defended—”

“By Livingston?”

“He’s a very able lawyer in the criminal sphere.”

“He’ll acquit young Weeks on a technicality and leave his reputation in tatters. In a case such as this, a case that touches on a man’s honor, it isn’t enough to create a doubt; one must leave no doubt.” As Alexander knew, all too well.

Harison looked sideways at him. “And then there’s Colonel Burr. . . . That’s the matter of it, isn’t it?”

Just thinking of the Manhattan Well made Alexander burn with rage. “You know well enough what his methods are.”

“I know well enough what yours are.” Harison let out a puff of breath, visible in the cold air. “Didn’t you just tell me yourself you’d promised Mrs. Hamilton not to exert yourself?”

“My Eliza would be the last to prevent me from exerting myself in a matter of justice,” said Alexander firmly, although when he remembered Eliza as she’d been that morning, exhausted, as close to defeated as he’d ever seen her, he wasn’t quite so sure.

There’d been a piece in the Aurora last week, claiming Alexander had been with his supposed mistress, Maria Reynolds, in Philadelphia. Eliza knew it was nonsense, of course. Alexander was reasonably sure Eliza knew it was nonsense. It was just another Republican dig, another attempt to discredit him, dragging up that old muck, the painful remembrance of his own misjudgment.

A case such as this would provide fodder of quite another kind for the papers. Burr and his Republicans had been making inroads with the lesser sort in the city, the small tradesmen and mechanics. Livingston was an ardent Republican; the two of them defending this Weeks boy would only entrench them as the champion of the little man.

But if Hamilton were joined with them in Levi’s defense . . . well, perhaps that might go some way to getting the Federalists the votes they needed to carry the spring assembly elections.

There was also the matter of the house. Ezra Weeks was one of the most sought-after builders in the city. If one were to build a house, one must have a builder. So it was really for Eliza’s benefit in the end if Alexander were to offer to Weeks to defend his brother.

And there was justice to be served too. It was really quite economical; he could annoy Burr, improve his own standing, benefit his party, thwart the mob, and forward the project of the house in the country, all at the same time.

“Would you have me leave an innocent to the mercy of the mob—and the eloquence of Livingston and Burr?”

“You know best,” said Harison doubtfully.

“Except when I do not?” Alexander clapped his old friend on the shoulder, his spirits rising dangerously; he could feel the excitement building, the thrill of a challenge. “You’ll introduce me to Weeks senior? I’ve had it in mind to build a house for Eliza. . . .”

“Oh, it’s about a house, is it?”

“I might just interest myself in his brother’s case.” Alexander looked seriously at his old friend. “I can’t leave a man to the mob, Richard.”

“Or the glory to Colonel Burr?” Relenting, Harison took his arm. “Come. We’ll leave these ghouls to their gawking. I’ll take you to Ezra Weeks.”

Excerpt. ©Lauren Willig. Posted by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Giveaway: 20 finished copies of The Girl from Greenwich Street

To enter Giveaway: Please complete the Rafflecopter form and post a comment to this Q: What did you think of the excerpt spotlighted here? Leave a comment with your thoughts on the book…

Meet the Author:

Lauren Willig is the New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of Two Wars and a Wedding, The Summer Country and Band of Sisters, as well as the RITA Award-winning Pink Carnation series. She’s also co-written four popular historical novels with Beatriz Williams and Karen White (Team W) as well as the newly published mystery The Author’s Guide to Murder. An alumna of Yale University, she has a graduate degree in history from Harvard and a J.D. from Harvard Law School. She lives in New York City.

erahime

What an interesting case. Thanks for the excerpt, HJ.

janinecatmom

I enjoyed the excerpt. It sounds like an interesting book.

Diana Hardt

I liked the excerpt. It sounds like a really interesting book.

Cheryl Hart

Awesome! I love that this is based on a true story.

debby236

I loved the excerpt and I love how there are so many varied books.

Mary C

Sounds interesting.

Daniel M

looks like a fun one

Saundra McKenzie

Really like the excerpt. Looking forward to reading the book.

Nancy Jones

I enjoyed the excerpt.

Amy R

What did you think of the excerpt spotlighted here? sounds good

bn100

interesting

Glenda M

I loved it and want more! Thanks!

Dianne Casey

Sounds like a great book. I like that Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr are part of the storyline. It’s on my TBR list, looking forward to reading the book.

Nancy P

Sounds like a captivating tale.

Shannon Capelle

This sounds so interesting

Patricia B.

Well written. Lots of period and cultural detail. I enjoyed it, and will enjoy the book.

lindaherold999

I love reading mysteries!