Today it is my pleasure to Welcome author Susan Meissner to HJ!

Hi Susan and welcome to HJ! We’re so excited to chat with you about your new release, The Last Year of the War!

Please summarize the book for the readers here:

Please share the opening lines of this book:

Los Angeles, 2010

I’ve a thief to thank for finding the one person I need to see before I die.

If Agnes hadn’t slipped her way into my mind to steal from it willy-nilly, I wouldn’t have started to forget things, and Teddy wouldn’t have given me the iPad for my birthday so that I could have my calendar and addresses and photos all in one place, and without the iPad, I wouldn’t have known there is a way to look for someone missing from your life for six decades.

It’s been a very long while, more years than I care to count, since I’ve spoken Mariko’s name aloud to anyone.

Please share a few Fun facts about this book…

- I’d decided on Davenport, Iowa, early on as one of the settings because of its heavy concentration of German immigrants but it had been a long time since I had driven through there; I needed someone on the ground to be my eyes and to make sure I got the setting details right. So I reached out on Facebook and asked if any of my followers were from the Quad Cities area and would they be willing to help me out with trips to the research section of the Davenport library and perhaps ask around about this and that, especially of the older generation. Someone responded who not only did those things for me, and happily so, but she who was a stranger became a friend. Karen and I got to meet up in a Chicago suburb not too long ago and we toasted our new friendship over the best deep dish pizza ever.

- Writing this book refreshed in my heart and mind very happy memories of the eighteen months my husband and I and our kids lived in southwest Germany back when my Bob was active duty Air Force. I remembered very fondly as I wrote, the delicious scent of fresh brotchen and how yummy the lebkuchen was and how the landscape there could be as beautiful as a Christmas card. I itched for a cup of Tchibo brand coffee and pfeffernusse the whole time I was writing about Elise’s time in Germany, especially when I wrote that the deprivations of war had them making coffee out of ground acorns.

- Until I researched apiculture for Chapter 12, I didn’t know beekeepers use smoke to dull the bees’ sense of smell so that the keeper is not perceived as an enemy. There really was an orange grove at Crystal City camp and there really were bee hives maintained by the internees.

If your book was optioned for a movie, what scene would you use for the audition of the main characters and why?

Because Elise’s relationship with her father is pivotal to the story, I would ask for this snippet. It’s also early in the book and won’t spoil anything for any of your readers. In this scene, Elise has just been reunited with her father Otto Sontag who’d been incarcerated at a camp for male detainees in North Dakota. But now dad, mom, Elise, and Elise’s little brother Max are on a train, together again after six long months, and they are bound for the family internment camp at Crystal City. Mom and Max have fallen asleep and Elise and Otto are speaking to each other in quiet tones. The scene is written in Elise’s point-of-view:

“Everyone back home thinks you are what the FBI says you are,” I said, cutting him off. “All the awful things they accused you of, everyone believes.”

Papa sighed and opened his mouth to say something, but I again filled the space with my own words.

“People back home treated Mommi, Max, and me like . . . like we had some disgusting disease they might catch if they got too close. I lost all my friends. Even Collette. Kids at school called me names, Papa. They called you names.”

“But names are not what we are, Elise.”

I didn’t doubt my father, and yet here we all were, on a train headed to a detainee camp, shades down, with an armed guard at the door—all because of the names Papa had been called: German sympathizer. Nazi lover. Insurgent. Infiltrator. Enemy.

“It feels like they are,” I said.

He was quiet for a moment. “It’s not always going to be like this,” he finally said. “The world is at war, and war is not . . . it’s not like any other time. I know this. I was fourteen, just like you, when my father came home from the Great War. It was a terrible time, those years he was gone, and it made no sense to me what everyone was fighting over. But it didn’t last. It ended. Wars begin and wars end. There will be peace again. We only need to hold on to who we are, deep within, so that we’ll recognize ourselves on the other side when it’s over. Do you hear what I’m saying?”

“Yes,” I said. I’d heard him, but I didn’t know what he meant, and he knew it.

“Don’t lose sight of who you are, Elise. Don’t give in to anger and bitterness.”

“But we did nothing wrong!” I said loudly. Max stirred on my lap and then quieted.

“Sometimes it’s not about right and wrong but now and later. Right now, we are having to put up with a difficult situation that we don’t deserve, and it’s not right. But later, when the war is over, we’ll remember that we didn’t let it break us. Hmm? Do you understand?”

There would be occasions, many years after this train ride, when I’d wonder if Papa believed he came out on the other side unbroken. But on that day, I chose to believe that it was possible. I nodded.

What do you want people to take away from reading this book?

I believe this story will give to its readers whatever they are willing to take from it. Much of what happened to fictional Elise and her family actually happened to real German-American families. Whenever we are exposed to events of the past, we have the opportunity to consider what those events mean to us. I can tell you what I came away with in the writing of this book, and that is that I know I still struggle like everyone else to always choose love over prejudice. I love this quote by Mother Teresa. “If you judge people, you have no time to love them.” It is so easy to make snap judgments and therefore so easy to be mistaken. It takes more time and effort to be kind and respectful and wise than it does to be afraid and prejudicial and hasty, but it’s worth the effort, I think. Especially when we’re talking about how we treat other people.

What are you currently working on? What other releases do you have planned?

The book I am just starting to tease out right now doesn’t have a title yet and is only in the roughest of rough draft beginnings, but it’s set in San Francisco in the early twentieth century. The lives of three women are going to converge because of the machinations of one man. The story is most likely going to begin with the discovery of a body, many years later…

Thanks for blogging at HJ!

Giveaway: Print copy of Susan Meissner’s THE LAST YEAR OF THE WAR

To enter Giveaway: Please complete the Rafflecopter form and Post a comment to this Q: How has the place where you were raised influenced your adult life?

Excerpt from The Last Year of the War:

I didn’t notice the shiny black cars—two of them—parked in front of our house. I came in through the side door like I usually did, to drop off my schoolbag in the little laundry room off the kitchen and hang up my coat. I knew that when my mother asked about my day, I wouldn’t be able to keep this from her. Nor did I want to. My mother was a tender soul, my father used to say, whose gentleness and honesty made you want to be gentle and honest. I had never lied to her before. She was going to ask me how my day was, and I was going spill it all to her. I would tell her that I tried to tell Mr. and Mrs. Hobart what Lucy had done, and she would ask why I didn’t tell someone at school hours ago. She would make a phone call and then I’d instantly become the girl no one could trust to keep a secret, and I’d likely get in trouble for not speaking up sooner. Telling my mother was the right thing to do, I knew, but my heart was pounding with the knowledge that my life was about to change.

I entered the kitchen, and my first thought when I saw my parents seated at the kitchen table—and a man in a suit standing over them with his arms crossed over his chest—was that they already knew. They knew about Lucy Hobart running away and that I’d been privy to this information since noon and had said nothing.

My father looked up at the man towering over them. “This is our daughter, Elise.” Papa’s voice sounded strange, as though he was nervous but trying to sound calm. Or scared but trying to sound brave. His German accent, usually so subtle as to be barely noticed, seemed more pronounced. My parents were fair-haired, too, like my little brother and me, though more honey brown than blond, and their eyes were gray-blue like mine. They were of average build and stature. Papa wore wire spectacles. They looked like ordinary Americans, and on most days sounded like them. But not today.

“Have a seat,” the man said to me, nodding to one of the empty chairs at the table.

“What’s happening?” I said, though I knew. I knew what was happening was that Lucy Hobart had run away and I’d had every opportunity to tell a teacher at school and I’d said nothing.

“Sit,” said the man, not unkindly, but not nicely, either.

“Do as you’re told, Elise,” Papa said.

My hands were shaking as I pulled out a chair. Mommi’s eyes were glassy as she looked at me, a fake little smile on her lips. She was probably already thinking of how to tell the policeman—for surely that’s who this man was—that I was not yet fourteen. Only a child.

It wasn’t until I had sat down that I heard scraping and toppling and shoving in other rooms of the house. Sounds of furniture being thrust about. Of drawers being open and shut. Of heavy shoes on the upper-story floorboards above my head. I glanced toward the ceiling.

“Who is upstairs?” I said. Surely they weren’t looking for Lucy Hobart in my bedroom. She was a grade above me. We weren’t even good friends. Acquaintances at most.

The man in the suit said nothing.

“Everything is going to be fine,” Papa said, in that same voice he had used to tell the policeman my name.

It was at that moment that I realized with sudden clarity that Papa was home from work at three o’clock in the afternoon. Perhaps this wasn’t about Lucy Hobart after all.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Book Info:

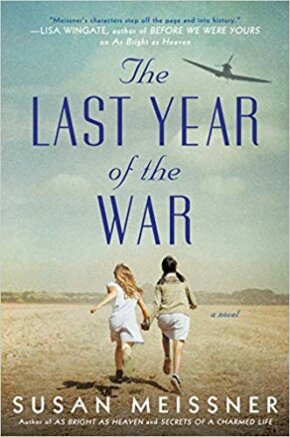

Elise Sontag is a typical Iowa fourteen-year-old in 1943—aware of the war but distanced from its reach. Then her father, a legal U.S. resident for nearly two decades, is suddenly arrested on suspicion of being a Nazi sympathizer. The family is sent to an internment camp in Texas, where, behind the armed guards and barbed wire, Elise feels stripped of everything beloved and familiar, including her own identity.

The only thing that makes the camp bearable is meeting fellow internee Mariko Inoue, a Japanese-American teen from Los Angeles, whose friendship empowers Elise to believe the life she knew before the war will again be hers. Together in the desert wilderness, Elise and Mariko hold tight the dream of being young American women with a future beyond the fences.

But when the Sontag family is exchanged for American prisoners behind enemy lines in Germany, Elise will face head-on the person the war desires to make of her. In that devastating crucible she must discover if she has the will to rise above prejudice and hatred and re-claim her own destiny, or disappear into the image others have cast upon her.

Book Links: Amazon| Barnes & Noble| Books A Million| Hudson Booksellers| IndieBound| Powell’s

Meet the Author:

Visit Susan at her website: susanmeissner.com or on Instagram as @soozmeissner, on Twitter at @SusanMeissner or at www.facebook.com/susan.meissner

Mary Preston

I was raised all over the country. I think that is perhaps why I am happy to stay put as an adult.

anxious58

Even as a kid I was more of an adult than a child, had to be to survive.

janinecatmom

I really don’t think it has influenced my life.

Debra Guyette

I lived in many places growing up as an Army brat. I find myself less concerned with where I live.

Jennifer Shiflett

I absolutely think it has.

Amy R

I was raised in a suburb and I found that I prefer smaller towns.

Danielle Hammelef

The place I was raised did influence my adult life because I prefer rural/small town life that I grew up in as opposed to big city life.

Lori R

I grew up in a college town and I now live in another college town.

dholcomb1

I was raised in a suburban college town. It gave me the possibility to dream.

diannekc

I feel that my hometown influenced the way I think about people and how important it is to be a good person.

granny2@outlook.com

I was raised in the country but I don’t think it inf!uenced me in anyway.

Mary C.

Judgments made due to my ethnicity – unfortunately, it hasn’t changed much but I am better at speaking up.

Tammy Y

Not sure

erahime

It has changed me definitely.

Melanie B

I think growing up in the small suburbs made me prefer a quieter, smaller living environment for sure.

Anna Nguyen

i grew up in the suburbs and that made me look for that when i moved and got a job, i like the close knit community

Shannon Capelle

Where I grew up my whole family lived and no matter where I have moved its still home. Its taught me to stay close to my family and work hard and traditions are important

BookLady

I grew up in the suburbs and have always felt more at home in that type of environment.

Katrina Dehart

It spurred my passion for history

Joy Isley

I grew up in a small town where everyone knew each other and talked to them. I talk to lots of people and enjoy their company. I guess it influenced me to be friendly

Jana Leah

I don’t believe where I grew up has had an influence on my adult life.

Natalija

Small towns tend to leave a huge impact. Everybody knew everything. At the time I cared about their opinion, but now I value opinions of only those who I care about and whose opinions matter.

Irma

I was raised in a country and because I lived a few years prior in the city, I could see how much living in the country afects me – in a much better way. I love working outside, I love the woods, I love looking like a Redneck woman, lol.

Daniel M

still live in the town i was raised

bn100

not sure

Dianna G. (@DedeZoomsalot)

I was raised near an army base. There were people from all nationalities and walks of life. Looking back, I really appreciate that diversity! Now I live in a small town where everyone is related. Very different!

Tina W

Grew up in Southern California, which was pretty diverse at the time. I think it helped me to be accepting of other people

Patricia B.

First I would like to thank you for writing this book. If it as good as it sounds, you have done many a great favor. I did not realize German-Americas were interred during WWII like the Japanese- Americans. It was criminal the way they were treated.

I grew up in northern New York in an area that was probably 80% Irish-American and French-American and very Catholic. For me at least, it was good to grow up with no “others” to be prejudiced towards. I learned to accept everyone for who they were. When an Air Force base moved in, bringing with it many people with different backgrounds, it was interesting and exciting to meet new people who had different experiences and backgrounds.

Terrill R.

I was raised in a small town that I moved away from as soon as I left for college, thinking I would never live in a small town again. After marriage and 2 children, I moved to a similar small town and appreciate the atmosphere and relative safety I experienced as a child.