Today it is my pleasure to Welcome author Parisa Akhbari to HJ!

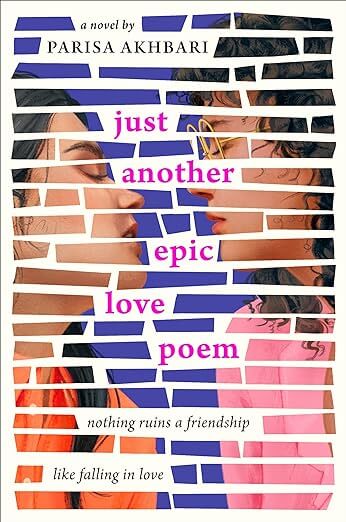

Hi Parisa and welcome to HJ! We’re so excited to chat with you about your new release, Just Another Epic Love Poem!

Hi, readers! Thanks so much for popping over for some Epic Love!

Please summarize the book for the readers here:

Please share your favorite line(s) or quote from this book:

“I know that ours is the realest kind of story: A story still unfolding. A never-ending thing.”

Please share a few Fun facts about this book…

Just Another Epic Love Poem was inspired by my experience as an Iranian American, closeted queer kid in Catholic school, so it’s full of big queer messy feelings! This novel is told through several different formats, including prose chapters, snippets of the never-ending poem verses that Bea and Mitra exchange, pages of Mitra’s poems written for her poetry seminar (with notes from her teacher included), text messages, lists, emails, and so on. The mixed media approach is one of my favorite things about this story! Another fun fact: Mitra and Bea have a set of rules for their never-ending poem, including no terminal punctuation (periods, exclamation points, and question marks are banned), and each girl has to start with the word that the last person ended on.

What first attracts your Hero to the Heroine and vice versa?

Mitra and Bea first meet in their eighth grade homeroom class, when Mitra transfers into Catholic school. She’s attracted to Bea’s ability to stand out even in a school full of uniform tartan jumpers and cross necklaces. She’s also drawn to Bea’s sense of humor and unapologetic authenticity. Bea, on the other hand, can tell that Mitra looks like a reader, someone who will appreciate the on-the-fly poetry verses she scribbles into her notebook.

Did any scene have you blushing, crying or laughing while writing it? And Why?

Mitra and Bea break into their school’s swimming pool for a plunge, and that scene really crackled with electricity as I wrote it. There’s this tension between the two of them that neither will name yet. A snippet:

THE BELL FOR second period rings as we make it into the athletics complex. For once, it’s me leading the way, Bea following. We pass the basketball court, surrounded by the thunder of dozens of gym sneakers.

“You know you’re late for French?” Bea glances at me. “And that’s in the other direction.”

“C’est la vie.” I push open the back door to the girls’ locker room. “Not going. But we can practice while we ditch, if you want.”

There’s a trace of pride in the way her eyebrows lift and her lips twist. Bea could make a scrapbook out of her tardy slips, but I’ve never cut class before. We dodge the open lockers and abandoned shoes and then, finally, I’m standing at the doorway to the pool.

“No!” Her face ignites with her grin. Whatever punishment might come of this, I already know down to my toes that it’s worth it to see the earlier hesitation drop from Bea’s face.

“It doesn’t open for swim practice until three,” I tell her. Only the blue light of the pool glows through the foggy window. “I’m going in.”

Bea pauses, just watching me.

“What?” I ask.

She’s seeing something in me. I want her to see, and yet I know I can’t let her.

“You gotta admit”—she gestures around my body like she’s feeling for my aura or something—“this is a new look for you. You’ve made it clear that you’re categorically opposed to water. Even on the holiest of occasions.”

“Last time I checked, the day you got your driver’s license wasn’t deemed a miracle by the pope.”

“It’s miracle-adjacent, though, right?” She wrinkles her nose at me.

Readers should read this book….

Readers should read this book if they’re fans of sapphic romance, queer coming-of-age stories, intergenerational family dynamics, themes of healing, trust, vulnerability, and forgiveness. Catholic school survivors and literary buffs are sure to feel a rollercoaster of emotions. If you’re looking for moments that will make you cackle with laughter and then fight back tears, this is for you!

What are you currently working on? What other releases do you have in the works?

I’m in the very early stages of planning my next queer YA novel, and in the meantime, I’m on tour, with upcoming events in Seattle and Bellingham, WA, Los Angeles, CA, Pittsburgh, PA, and more–check out my website at www.parisawrites.com for a full schedule! I’m also anticipating a writing-in-residence at Hedgebrook on Whidbey Island, where I’ll be drafting my next novel.

Thanks for blogging at HJ!

Giveaway: 1 finished copy of JUST ANOTHER EPIC LOVE POEM. US only.

To enter Giveaway: Please complete the Rafflecopter form and Post a comment to this Q: My characters make meaning out of the hard stuff in their lives through writing and reading poetry. How do you find yourself channeling the tough experiences in your life?

Excerpt from Just Another Epic Love Poem:

BEA AND I were thirteen when we met, when I transferred into her eighth-grade classroom at Holy Trinity. Bea would fight me on this part, but our friendship—and everything after—began with her pelting me in the back of the head with a wad of paper.

Not that I was a stranger to fielding other people’s spitwads. But my first day had already been off to a miserable start, mainly because of the uniform jumper. It hung in this thick, carpet-like fabric down my body, a pleated headache of red and gold plaid.

This is the first day of the rest of your life, I thought. I looked like a human Christmas tree ornament. And maybe that was the point of Catholic school. How would I know?

We had just moved to Crossroads, the one almost-affordable pocket in the uber-rich city of Bellevue, Washington. I loved our new neighborhood because of its proximity to the Crossroads Shopping Center, home of the only Iranian-owned pizza parlor I had ever heard of. I also loved it because we were surrounded by other brown people. Crossroads felt like a little belly button of familiarity in a giant and strange new city.

But our new school wasn’t in Crossroads. It was in Medina, where everyone had a home tennis court or a pool. And it wasn’t like my old school, which my dad referred to as a “crunchy hippie place” when he found out I spent science class sifting through trash bins to start a composting system. Holy Trinity was a private Catholic school.

Which was a weird choice, given that my dad was raised Muslim.

Dad had ushered my eleven-year-old sister, Azar, and me into our new student orientation with a pep talk about how Catholics valued education above all else, and how the teachers would only care that we studied hard. I guess he believed that good grades would shield us—like nobody would notice that we were clearly Iranian American,

and didn’t know a thing about Catholicism, because intellect would render us into amorphous orbs of knowledge.

The idea of Catholic school had me convinced I’d be transported into a staging of The Sound of Music, nuns and all. From the brochures, the entire student body of Holy Trinity looked like a beaming sea of von Trapp children. I half expected them to twirl around in their matching jumpers and suit coats and serenade me with “Do-Re-Mi”

on my arrival.

Turns out, didn’t happen.

Dad pulled up to the school grounds that first day, sneak-attack kissing my and Azar’s foreheads. “Make it a good day,” he shouted as we slipped out of the car, his accent snagging the attention of some tall boys in blazers. “Make it the best day of your life!”

That’s how Dad said goodbye to us every day since we left Mom—a charge to make the best of crappy times.

Azar and I headed toward the complex of brick buildings, and she immediately broke away from me, flocking toward a gaggle of sixth grade girls on the lawn. I kept my eyes on the scattered leaves in front of me, not looking up until I reached the arch at the school’s entrance, which was engraved with the words: May God Hold You in the Palm of His Hand.

Each building on campus was named after a Jesuit priest or saint, their faces embossed above the doors so that some old, dead white guy was always scowling down at you upon entry.

Xavier—or Creepy Goatee Dude, as I came to think of him—was cavernous, with a long, dark hallway parting two rows of lockers. The space was packed with students huddling by their respective lockers, every single one of them glued to a phone. The front door thudded behind me, and some of the kids looked up, glaring, before

going back to sending their last messages before first period. I didn’t even have my own phone; Azar and I shared my dad’s old Galaxy, which meant she was constantly wresting it out of my hands so she could play Pet Rescue Saga or video chat the gazillion friends she left behind in Sacramento. I didn’t need my own phone, because I didn’t have anyone to talk to.

As I worked my way toward the classroom, I snuck glances of the Holy Trinity girls. They all looked so shiny and wholesome, like they ate apple pie every night and said prayers and flossed their teeth before bed. Some of them had cross necklaces over their jumpers, and they were all wearing knee-high socks, not the crew-cut ones my dad had picked out for me at the sporting goods store. I’d have to ask my dad for a cross necklace so I could go incognito for as long as humanly possible. I wondered how soon it would be before everyone found out that Azar and I weren’t Catholic.

Behind the door of Ms. Byrne’s eighth-grade classroom, thirty-three sets of eyes zeroed in on me. This was the problem with transferring to a new school in October: Everyone had already established a routine, and here I was, shattering their normalcy with my unfamiliar face and my weird crew-cut socks. I tucked into a desk in

the corner of the classroom and stared at the crucifix by the doorway.

Jesus, blue-eyed and bleeding, hung stretched out on the cross. Beads of red paint circled the nails in his palms and feet. His head lolled to one side under a crown of thorns. It struck me as pretty graphic for a school where you weren’t allowed to expose your collarbones or wear nail polish.

“Jesus was a nice guy,” my dad had told me when I asked him why we were going to Catholic school. Lots of Christians don’t know this, but Jesus was revered as a prophet in Islam, and there is even a whole chapter in the Qur’an named after Mary. But I had never seen a dead body like this before, sculpture or otherwise. It made me rethink the cross necklace idea.

“Peace be with you, class.” A light-skinned woman with smooth brown hair broke my focus. She wore a gold blazer and knee-length skirt with a red-and-gold tie. Going off her outfit alone, I could tell she was nothing like my old teacher Edgar. He smelled like pipe smoke and his jeans were chronically mud-stained from helping us collect

earthworms for our compost project. Anytime one of us shoveled up a worm from the garden patch, he’d say something ridiculous like “Ya dig it?”

Ms. Byrne pulled out a clipboard for roll call, and I allowed myself to peek at the other students as their names were read aloud. Tristan? Leah? Savannah? Matthew? Spencer? All of them wore red jumpers or blazers, and they all whirred together in my brain like one of Azar’s berry smoothie blender experiments.

“Beatrice?”

My eyes wheeled to the row behind me. Beatrice teetered on the back legs of her chair, the metal frame creaking beneath her. She wore round glasses, her knee-highs were mismatched, and her haircut was definitely of the DIY variety. And still, somehow, I knew she was cooler than me. Not popular, I guessed, but memorable. Other kids looked to her when her name was called.

She met my eyes. “Bea,” she said to Ms. Byrne—and also, it seemed, to me.

“We don’t use nicknames at school, Beatrice,” Ms. Byrne said, returning to her list. “Oh yes, that’s right. We have a new student joining us today.” The teacher scanned the back of the class and landed on me. “Mitra . . .” She stalled. “How do you say this?”

My voice was stuck in my gut somewhere beneath the shir berenj I’d had for breakfast. “Esfahani.”

Bea was still watching me. Her skin was amber-brown like mine, but with dark freckles dusting her nose.

“Es-fa-ha-ni.” Ms. Byrne jotted down a pronunciation note on the roll call sheet. She was trying to be helpful but had already spent ten more seconds focused on me than I could handle. “What kind of name is that?”

As she asked, it occurred to me that I should’ve practiced answering these kinds of questions at home. Then I’d be a pro at deflecting any inquiries into my background. Like Wonder Woman, when she used her bracelets to deflect hundreds of whizzing bullets.

But I didn’t have magic Amazonian bracelets, so I winged it. “It’s, um, a last name?”

Bea laughed so hard that it verged on inappropriate.

“Okay,” Ms. Byrne said, mercifully choosing to move on. “Welcome, Mitra.”

She set down her roll call sheet and faced the class. “Today we’re going to continue our unit on poetry. Page one eighty-one, Billy Collins’s ‘Litany.’”

Everyone except me pulled out thick textbooks and flipped through the pages. I glanced at the girl next to me, who had red ringlets over her eyes. I could make out some of the poem on the page of her open book, but when she caught me looking, she blocked my sight with her elbow.

“Follow along with me,” Ms. Byrne said.

I dug my thumbnail into the wood of my desk. The poem started like this:

You are the bread and the knife,

the crystal goblet and the wine.

It continued describing its subject through metaphors like that,

bringing images of birds and bakers and bright sunshine clear into

my mind. And it named what the subject is not: not the plums on the

counter, certainly not the pine-scented air.

When she finished the poem, Ms. Byrne lifted her eyebrows at us. “Reactions?”

Bea’s hand shot up.

“Yes, Beatrice.”

“I like the images. I like the ‘burning wheel of the sun.’ But, who does this guy think he is?”

“Pardon?”

“He keeps saying ‘You’re this, you’re that, you’re definitely not that,’” she said. “What if I am the pine-scented air? Where does he get off thinking he can tell me what I am? He doesn’t know my life!”

A boy behind me chuckled.

“All right, Ms. Ortega. Calm down,” Ms. Byrne said, pinching the bridge of her nose. “Time for small group discussions. Pair up with your partners and share your responses to ‘Litany.’ I want you to identify how Billy Collins uses the elements of poetry we’ve been learning about: form, sound, imagery, metaphor.” A teacher’s aide knocked at the door, and Ms. Byrne stepped out of the room.

Everyone turned toward the kid next to them, and I just sat there, not sure who my partner was supposed to be.

“I have to work with the new girl,” the redhead beside me whispered loudly to a girl across the aisle from her.

Her friend groaned. “Don’t work with the new girl,” she whined. “Work with me.”

My chin sunk toward my chest, and my eyes locked on the crucifix again. It would be a lot easier to blend in if I at least had a textbook to look through. I kept hearing my dad’s voice in my head: Jesus was a nice guy.

Then, flick. Something soft bounced off the back of my head.

Excellent. My first day at Holy Trinity, and my head was already serving as the backboard for someone’s private game of basketball. The kids around me stopped chattering, and I took in a slow breath. Then I twisted around in my seat and found it: a wad of crumpled paper. I kept it closed in my palms and slumped back into my chair.

“Hrrm,” someone coughed. “Hrrrm!”

It was Bea. When I looked at her, clueless, she rolled her eyes and then made a gesture with her hands, like she was unfurling a scroll.

I stared back at her for a moment too long. Then I opened my hand and smoothed out the paper against the edge of my desk. Tiny purple writing emerged from the inside of the page.

They say you’re just the new girl

but they should know better,

you’re really the jelly

holding the sandwich together,

I’m a thunderclap

not some goblet of wine,

Holy Trinity sucks

but at least my poem rhymed.

—Bea-lly Collins

Ms. Byrne came back, and I hid Bea’s note in a pleat of my jumper.

Nobody had ever written me a poem before. Unless you counted the improvised rhymes Azar liked to scream at me whenever she was mad, like Mitra’s alone sitting in a tree, F-A-R-T-I-N-G! But those were more spoken word performances than actual poems. When I finally worked up the courage to look back at her, Bea tilted her head to one side and lifted an invisible pen in her hand, scrawling imaginary cursive in the air.

She wanted me to write back.

When Ms. Byrne turned to the whiteboard, I inched Bea’s poem out of the pleat in my skirt and scribbled something down. When my moment arrived, I chucked the paper ball back at Bea. She unfolded it immediately.You’re the thunderclap

and the flash of bright light,

I’m the bunny down below

watching the sight,

I’m sorry to tell you

but I think we’re outmanned

we are both held hostage

in The Palm of God’s Hand.A grin broke across her face, lifting the rims of her glasses.

There was a flicker, even back then—one tiny flash of feeling in the empty shell of my chest. I called it relief.

I didn’t know to call it love.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Book Info:

Over the past five years, Mitra Esfahani has known two constants: her best friend Bea Ortega and The Book—a dogeared moleskin she and Bea have been filling with the stanzas of an epic, never-ending poem since they were 13.

For introverted Mitra, The Book is one of the few places she can open herself completely and where she gets to see all sides of brilliant and ebullient Bea. There, they can share everything—Mitra’s complicated feelings about her absent mother, Bea’s heartache over her most recent breakup—nothing too messy or complicated for The Book.

Nothing except the one thing with the power to change their entire friendship: the fact that Mitra is helplessly in love with Bea.

Told in lyrical, confessional prose and snippets of poetry Just Another Epic Love Poem takes readers on a journey that is equal parts joyful, heartbreaking, and funny as Mitra and Bea navigate the changing nature of I love you.

Book Links: Amazon | B&N |

Meet the Author:

Parisa Akhbari (@authorparisa) is a mental health therapist and writer from Seattle, Washington. Her debut YA novel, Just Another Epic Love Poem, follows two queer best friends in Catholic school as they fall in love through the pages of a never-ending poem they’ve been writing back and forth for five years. When not writing or therapizing, Parisa can be found trying to replicate her grandmother’s drool-worthy Persian recipes, riding ferries around the Puget Sound, and dancing around the kitchen with her wife and dogs.

Website | Twitter | Instagram |

erahime

Through mental health assistance, journaling, reading, and surrounding myself with patient listeners.

psu1493

Journaling

Diana Hardt

Through reading.

Amy R

How do you find yourself channeling the tough experiences in your life? reading, listening to music and baking/cooking

Daniel M

drinking beer

Dianne Casey

Trying to relax. Reading and my cats help.

bn100

eat

Nancy Payette

Hibernation